With state-of-the-art microscope, students turn nano imagery into art

Open gallery

Striving to build a nanoscience program in the liberal arts tradition, Lewis & Clark professors have emphasized a unique interdisciplinary approach. Garrick Imatani, assistant professor of art, and Anne Bentley, assistant professor of chemistry, used a high-powered microscope to help their students from disparate fields of study explore nanotechnology through art.

Students from Imatani’s 3-Dimensional Foundations class and Bentley’s Nanomaterials Chemistry class paired up to use a new Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) to generate sculptural installations. Students were asked to examine the implications of using technologies to generate art that no longer depends on images, shapes, or colors that are visible to the human eye.

“The great advantage of being at a smaller school like Lewis & Clark is that these kinds of collaborations can happen fairly easily,” said Bentley, a nanotechnology expert. “I was drawn to work at a liberal arts college in part because I am interested in the interactions between science and society or between science and other fields of study.”

The best light microscopes, those routinely used in introductory biology classes, can magnify to about 1,000 times and have limited depth of focus. The SEM, which was purchased through a $250,000 grant from the W.M. Keck Foundation, can magnify an image up to 24,000 times, and the technology allows for much better focus across many layers of a sample to create exceptional three-dimensional images.

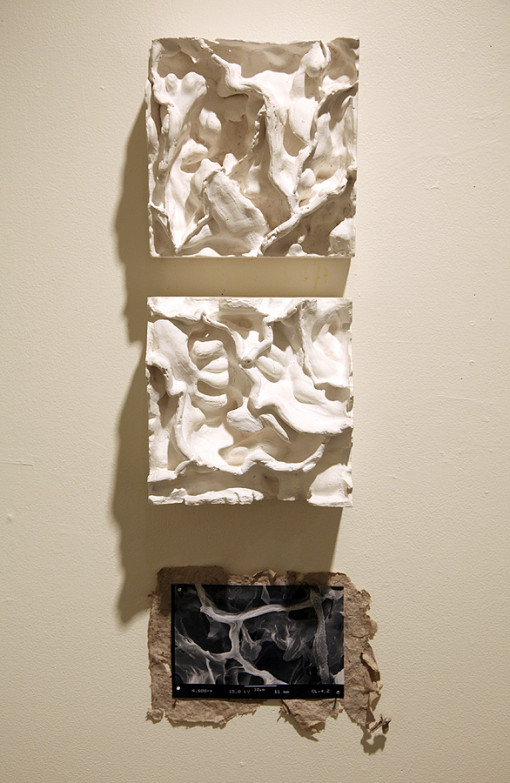

Students worked with varied materials, drawing artistic inspiration from everyday items to create their relief and cast artwork.

-

Diego Herrera used a scan of a broken vinyl record as the visual reference

Diego Herrera used a scan of a broken vinyl record as the visual reference -

Miranda Lancaster-Moore scanned handmade paper she made from foraged mushrooms

Miranda Lancaster-Moore scanned handmade paper she made from foraged mushrooms -

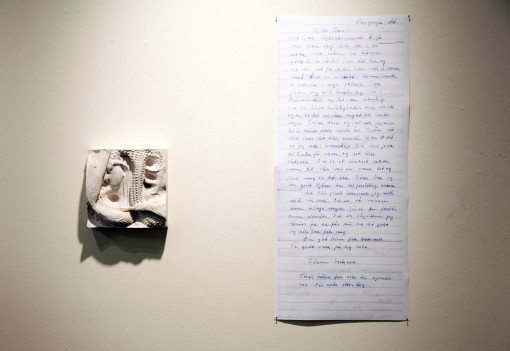

Thea Strom scanned torn pieces from a letter from her grandmother in Norway

Thea Strom scanned torn pieces from a letter from her grandmother in Norway

Here, Imatani and Bentley discuss the value of this unique collaboration and why this cross-pollination of disciplines is useful to both the arts and sciences.

What is the value of a collaborative project that brings together such diverse fields?

Bentley: A goal of mine was to incorporate a wide variety of activities into our class time. While the class was not a lab course per se, I wanted to take advantage of the new microscope to give the students a more visual connection to what we were learning about how scientists gather information about the chemistry of small materials. Also, because educational research has shown the value of teaching in aiding learning, I wanted to put my students in a position where they would be explaining the microscope to a non-scientist.

I asked my students to write a one- to two-page reflection about the project after it was over. The words they used to describe the final installation included words such as unbelievable, surprising, incredibly exciting, amazing, and eye-opening.

Imatani: There is value in collaboration itself and especially in terms of interdisciplinary exchange. I try to instill in my students that art is not formed in a cultural vacuum. The more that students can draw on the research and knowledge of other disciplines, the more rich and informed their work will be. For example, artists have been relying on the wavelengths of light and central perspective since the Renaissance within the framework of classical portraiture. But what happens when we no longer need light to generate an image, as exemplified by the Scanning Electron Microscope? Artists have been using technological aids to aid in portraiture for over a thousand years, and yet, our methods and techniques have become completely ossified out of historical tradition. I’m interested in asking my students what our “portraits” might look like if we adopt the spirit and attitude of earlier artists to incorporate the technological advancements of imaging into their idea of portraiture or documentation of a cultural moment.

Anne, as a scientist and teacher in the field of science, how much had you thought about the intersections between art and science before this project?

Bentley: There are a number of ways in which art and science intersect, and I’ve always kept an eye out for interesting examples. I like to think of the intersections in two categories: “the science of art” and “the art of science.” I have been less exposed to the art of science, but I am aware of Felice Frankel’s work in Boston with the chemist George Whitesides at Harvard. Frankel’s photography is beautiful. There is also large field of conservation science in which scientists study the chemical processes of how art degrades over time and try to develop ways to conserve art.

Garrick, as an artist, do you think there is a growing understanding between the fields of art and science or an interest in learning from each other more? Does art influence science and does science influence art?

Imatani: I’d say the influence has never disappeared in terms of artists’ fascination with science. Historically, it has been more of a one-way street in that scientists borrow less from the artistic traditions. However, even as I say that, I pause. At this point, the term “science” is so broad and all-encompassing that I feel uncomfortable even talking about science as an entity onto itself that is somehow wrested from conversations of aesthetics or politics. I received my academic training through an interdisciplinary framework, so it’s hard for me to see disciplines as ideologically divested from one another to begin with.

As a more concrete and perhaps helpful example of this disciplinary overlap, I’d point to Elizabeth Kessler’s research, which draws connections between the Hubble Space Telescope images to the tradition of Western landscape painting. The Hubble images come back as black and white data, and yet in interviewing the scientists responsible for manipulating the data into color form, she has discovered that there is quite a lot of subjective coloration and cropping that goes into the production of those images that rely on many aesthetic predispositions and expectations rooted in the tradition of romanticism.

Were there any challenges to figuring out how to collaborate? Did you find yourselves identifying differences in approach that are endemic to an artist and scientist, or was it an easy collaboration?

Bentley: Absolutely—we had a number of logistical challenges to overcome and basically made it work by staying in touch on a near-daily basis throughout the project. At one point, Garrick sent me a copy of the material he’d given his students describing his expectations for the final installation. Garrick would tell you that he thought it was quite proscriptive, but when I shared it with my students, they though it was still quite vague. This was really interesting for all of us—it made us on the science side realize how much we like order. Grading science assignments is often fairly black and white. I think the less quantifiable aspects of the assignment were more of a challenge for my students.

On June 29, Bentley and Imatani will present at the Northwest regional meeting of the American Chemical Society as part of the symposium “Collaborations and Communities to Improve Teaching and Learning in Chemistry.”

This spring, Imatani and Bentley gave a presentation at the Foundations in Art: Theory and Education conference held in St. Louis.

More Newsroom Stories

Public Relations is located in McAfee on the Undergraduate Campus.

MSC: 19

email public@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7970

Public Relations

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road MSC 19

Portland OR 97219