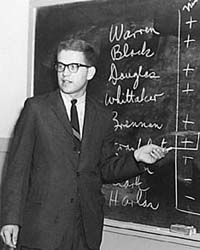

Professor works to build a just society

Open gallery

One late evening, following a day of intensive study at the University of Washington, Donald Balmer sipped coffee with his good friend Ancil Payne.

“This was an era, during World War II,” Payne recalls, “when students, and particularly veterans, were deeply concerned about world order and social justice.”

Balmer, who began his studies in engineering, had switched his major to political science because he wanted to build something bigger than a bridge—he wanted to construct a decent society, Payne says.

As the two college friends debated their future careers, Balmer argued for joining the political fray in order to change society. Payne advocated for a career in education and teaching “to influence hundreds, possibly thousands, ultimately changing society.”

In the end, Payne was the one who entered the political life as a partisan organizer and congressional assistant while Balmer took up teaching.

“And, thank God for Don’s decision,” Payne wrote. “Don has stimulated student thinking, opened young minds and, through the past half-century, advised for the better, those in the political trenches.”

Balmer’s former students include U.S. Rep. Earl Blumenaurer ’70, JD ’76; Larry Campbell ’53, twice speaker of the House in the Oregon legislature; Don Bonker ’64, former U.S. Congressman from the state of Washington; and Serena Cruz ’89, Multnomah County commissioner.

When World War II broke out, the Navy shipped Balmer to a training program at the University of Washington. “So when the war was over, I was ahead of everyone in terms of my education.” Balmer, who was just 24 years old when he joined the Lewis & Clark faculty, recalls that the student body president was older than he was.

The campus was only nine years old and had few buildings—those that were part of the original Frank Estate, war surplus buildings, a gym, half of BoDine and Akin Residence Hall. Balmer earned $3,700 during his third year on the job. Even so, he says, each member of the tight-knit community gave a dollar to support a foster child. The small campus fostered lifetime friendships.

“People in my generation lived in a golden age,” Balmer believes. “We remember the Depression. World War II was disastrous for many, but it was a ‘just’ war if there ever was one. We’ve seen the postwar prosperity. We’ve seen improvements in civil rights, civil liberties, environmental concerns, the arts and health care. It’s been a wonderful time.

“I have had all the luck,” he adds. “That includes having an exceptional wife who shared in campus activities and overseas study programs and having four sons who also benefited from campus connections.

“It’s been an unspeakable privilege to share in the continued building of this College,” Balmer says, citing the satisfaction that has come from helping to shape a community, taking part in a wide variety of activities, meeting with visiting scholars and public figures, working with “really good human beings” and preparing students to build a just society.

He remembers the first time he took students to Washington, D.C., “I was on the balcony in the Library of Congress watching students studying intensely. I thought, ‘I could die happy right now, seeing what these students are doing.’”

Balmer shares another favorite story. “It happened in my American government class,” he says. “I arrived about 9 a.m., and students were standing outside the room. I tried my key, but it jammed. So, I called facilities services and told the students, ‘Stay here. I’ll find an empty room.’

“When I came back, there were only two or three students standing outside the room.

“‘Where are the rest of the kids?’ I asked.

“‘They are in the classroom,’ they answered.

‘”Is the door open?’ I asked.

“‘No,’ they said. ‘They climbed through the window.’

“Now,” Balmer asks, “When is the last time students broke into a classroom to go to school?”

More L&C Magazine Stories

Lewis & Clark Magazine is located in McAfee on the Undergraduate Campus.

MSC: 19

email magazine@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7970

fax 503-768-7969

The L&C Magazine staff welcomes letters and emails from readers about topics covered in the magazine. Correspondence must include your name and location and may be edited.

Lewis & Clark Magazine

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road MSC 19

Portland OR 97219