An Artful Collaboration

Open gallery

On a rainy fall day, Lewis & Clark’s Aubrey R. Watzek Library is a refuge from Portland’s gray weather. Designed to house books and journals, the soaring, light-filled space could double as an art gallery. Brilliant wall hangings, carved artifacts, and framed pieces catch the eye in public areas and liven up the stacks.

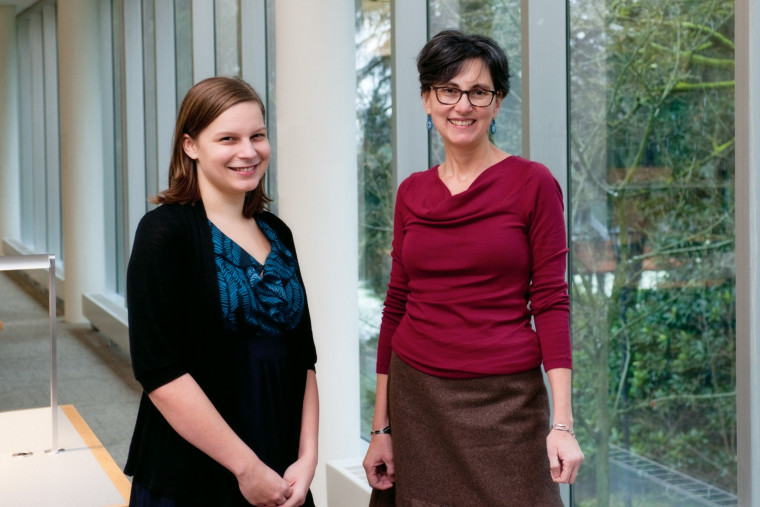

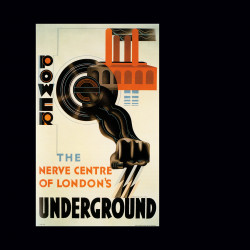

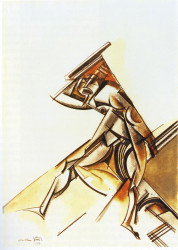

Most of this visual bounty was created by professional artists. But one current exhibit, located just off the library’s main lobby, is by members of the Lewis & Clark community: Rishona Zimring, associate professor of English, and Casey Newbegin BA ’12. Professor and student cocurated E. McKnight Kauffer, Gwen Raverat, and the Illustration of Modernity using materials from the Watzek Library’s Special Collections. The exhibit brings together a variety of materials, from advertising flyers to travelogues, that reflect British modernism—the culture of Great Britain between the two World Wars.

Selecting and arranging materials for the exhibit brought together strands from Zimring’s established work with Newbegin’s budding scholarly interests. The project also called for the academic and technical knowledge of the Special Collections and Archives staff. All the participants contributed unique expertise to the project, their roles intertwining to create a robust scholarly experience. The exhibit, which is on display through May 31, also represents a gift to library visitors in the 2012–13 academic year.

According to retired William Stafford Archivist Paul Merchant, Zimring is among the Lewis & Clark faculty who use Special Collections most actively. “Rishona is eager to have students use our resources,” Merchant says. It was no surprise, then, that Zimring became interested in exhibiting some of those materials to the larger community. Creating a library exhibit also fit with Zimring’s expertise as a literary scholar, because the exhibit includes as many words as images. “It’s a great hybrid of text and visuals,” she says. “And a college library is the perfect venue because this exhibit is designed to teach as well as to entertain the eye.” Finally, Lewis & Clark’s strong support for faculty scholarship creates a rich academic environment that informs faculty members’ engagement with students. Zimring completed the research for her forthcoming book, Social Dance and the Modernist Imagination in Interwar Britain (Ashgate Press), at the same time as she and Newbegin were curating Illustrating Modernity. Zimring’s research for the book involved visual and theatrical materials, including archival materials such as the stage designs of Gwen Raverat. Being an active researcher shaped Zimring’s thinking about the exhibit, enriching her work with Newbegin as well as the end product.

Professor’s Interests Enrich Library Collections, Courses

These acquisitions helped lay the groundwork for the current exhibition. As Merchant and Zimring worked together to develop the library’s modernist holdings, they began discussing ways to share the materials with the Lewis & Clark community. Special Collections mounts regular exhibitions based on its holdings. Assistant archivist Jeremy Skinner explains, “We do one exhibit per semester, and try to feature materials from Special Collections as a way of letting people know what Lewis & Clark has.” Merchant had recently worked with English department faculty Pauls Toutonghi and Andrea Hibbard and junior Dana Bronson on an exhibit about Charles Dickens, so the precedent for student-faculty collaborations with Special Collections was established. Mounting an exhibit on British modernism seemed like a natural choice.

Student Finds Her Career in the Library

Zimring and Merchant began discussing an exhibit of modernist materials in early 2010. Around the same time, Newbegin began working in Special Collections as a work-study student. She explains that the previous fall, Merchant had visited one of her courses and happened to mention that Special Collections employed work-study students to help digitize and organize the collections. “It was like a lightbulb went on,” says Newbegin. “Before that, I didn’t really know Special Collections existed and had never considered archival work, but it just seemed perfect.” She approached Merchant after class and went to work in Special Collections a few months later. The experience confirmed her newfound interest: “The staff were welcoming and helpful. They tried to give me projects I was interested in personally and create an experience that would benefit my education,” she says. “Working in Special Collections was when I really started getting excited about archival science.”

In fall 2010, after she had been working in Special Collections for several months, Newbegin enrolled in Zimring’s course on James Joyce and Virginia Woolf. She developed a scholarly interest in Woolf and her husband, Leonard, and applied for the English Department’s Dixon Award to study their work in England. Newbegin was a cowinner of the award, and spent two weeks in summer 2011 at the University of Sussex in Brighton, England, where she studied Leonard Woolf’s personal files in the university’s archives. She also visited museums and heritage sites, including the Woolfs’ home, Monk’s House. “I got to handle Leonard Woolf’s diaries, wander around the couple’s garden—it was amazing,” Newbegin says. “I immersed myself in the archival material and the Woolfs’ world.”

The experiences of working in Special Collections and conducting her own archival research confirmed Newbegin’s belief that she had found her calling. They also made her the perfect student collaborator when Zimring decided to proceed with a modernist exhibit.

Archivists Lend Support and Rare Materials

When Merchant and Zimring discussed creating an exhibit, they faced a logistical problem: Special Collections staff were busy preparing the massive William Stafford bibliography for publication. “We agreed to do the exhibit if Rishona took responsibility for choosing the materials and writing the explanatory text,” Merchant says. Zimring, like many Lewis & Clark faculty, often collaborates with students on academic research. She and Merchant both thought of Newbegin, who had both archival experience and a strong scholarly interest in British modernism.

In creating the exhibit, the student-professor team took on duties normally handled by the archivists. For example, assistant archivist Skinner typically designs the exhibit catalog. This time, Newbegin worked on design, printing, and production with help from Skinner, including a template the library had used for similar exhibits. Skinner also brought technical expertise to the project, making sure that rare pieces were appropriately handled and, in some cases, reproduced so the originals could remain in storage. “This exhibit is highly visual,” Skinner says. “We wanted to make sure we could provide maximum visual impact to viewers while preserving our collection.” Working side by side with an archivist on the practical details of an exhibit gave Newbegin even more experience in handling rare and valuable materials.

Collaborating on a Finished Product

Newbegin started work on the exhibit in February 2012 and continued to work on designing and installing the materials over the summer. In her section of the catalog (Zimring wrote the others), Newbegin drew on what she had learned about British modernism in her studies with Zimring and abroad. Because of her strong interest in the Woolfs, she particularly enjoyed creating a display about Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s responses to their first car, including photographs, travel accounts—including notes from their trip through Nazi Germany—and a model of their Lanchester Singer automobile.

The project had challenges as well as pleasures. “‘Illustrating modernity’ is a broad topic, with a lot of interconnected subject matter,” Newbegin says. “The deeper Rishona and I dug, the more connections we saw. So part of the challenge was narrowing down what we chose to include.” She credits Zimring with encouraging her to examine many items to find the most appropriate for display. Newbegin also believes the project enhanced her academic work. “Lewis & Clark doesn’t create concentrations within majors, but I ended up with a kind of self-made concentration in 20th-century British literature. I gained a significant amount of knowledge on one subject and even tied it in with my honors thesis.”

Despite the months of intense work required, working on the exhibition has only increased Newbegin’s passion for archival materials. “Sometimes students don’t realize what amazing stuff is tucked away in the library,” she says. She plans to earn her master’s in library science and become an archivist and is hoping to study at the University of Texas at Austin.

Newbegin was not the only student to benefit from Illustrating Modernity before it opened to the public. Zimring brought students from a 300-level British literature course to Special Collections to examine the materials assembled for the exhibition. Then she asked students to do research based on the materials, returning to Special Collections on their own to find answers.

“The feedback was very positive,” Zimring says. “Working in the archives was new to students, but they found it enjoyable and enlightening. In addition, I enjoy learning from the students’ inquiries. Teaching is never a one-way exploration because students bring fresh ideas to the material.” Such a synthesis of faculty research and undergraduate learning is “a tribute to Lewis & Clark, which encourages faculty to be both active scholars and good teachers”—and provides opportunities for students to become researchers.

Genevieve J. Long is a freelance writer in Portland.

More L&C Magazine Stories

Lewis & Clark Magazine is located in McAfee on the Undergraduate Campus.

MSC: 19

email magazine@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7970

fax 503-768-7969

The L&C Magazine staff welcomes letters and emails from readers about topics covered in the magazine. Correspondence must include your name and location and may be edited.

Lewis & Clark Magazine

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road MSC 19

Portland OR 97219