Grit and Grace

Through his documentary films, Brian Lindstrom BS’84 brings marginalized lives to light.

by Ben Waterhouse BA ’06

It is easy, in a stressful situation, to make one deadly mistake: a warning ignored, a brake pedal missed, a trigger pulled too soon. But the death of James Chasse Jr. was not the result of a single mistake.

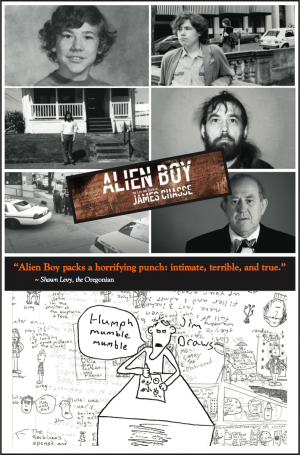

As documentary filmmaker Brian Lindstrom BS ’84 relates in Alien Boy: The Life and Death of James Chasse, the 42-year-old Portlander, who died in police custody in 2006, was the victim of a series of increasingly terrible and unnecessary choices.

“I think we’re used to viewing a lot of police tragedies that are unfortunate one-time decisions about pulling a trigger,” Lindstrom says. “What’s so disturbing about this [case] is that the film reveals this cascade of deceits, omissions, and lies that lead to this terrible death, which was preventable.”

Alien Boy premiered in February at the Portland International Film Festival after six years of production. Through videotaped depositions, court documents, and witness interviews, the film lays out the events of the two hours that ended Chasse’s life. On September 17, 2006, Chasse, who had schizophrenia and a lifelong fear of police, was approached by Portland officers who thought he was behaving suspiciously. When he ran away, the officers tackled him hard enough to break 16 ribs, then declined to send him to a hospital. Instead, they carried him, hog-tied and screaming in pain, to the Multnomah County Detention Center, where he was left in a cell, stopped breathing, and was finally put in a squad car headed for Providence Medical Center. He died in transit, a few minutes away from the emergency room.

But Alien Boy is more than a grim procedural—it is also a sensitive portrait of Chasse, a musician, writer, and cartoonist who was a fixture of Portland’s early punk scene (the film takes its title from a song written about Chasse by the Wipers). Despite decades of mental illness, Chasse lived a meaningful, artistic life. He was deeply loved by his friends and family, who called him Jim Jim. Lindstrom calls Chasse “an amazing success story” of the mental health system, who had “a beautiful, sensitive, fragile-yet-resilient nature.”

Lindstrom has spent years documenting the lives of people he says “society kind of puts an X through,” so it’s no surprise he imbued Alien Boy with empathy. Throughout his career he has strived, in his own words, to “expose some grit and grace, that otherwise you might not know was there, in the people you may walk by every day.”

—

In the days before the digital revolution made filmmaking accessible to everyone, learning to make films wasn’t as easy as it is today. “It wasn’t like most people had cameras or editing software,” Lindstrom says. He made little headway during his first year of college at the University of Oregon, or his second, on a National Student Exchange program at Rutgers University. Looking for a “nice little liberal arts college” experience, he transferred as a junior to Lewis & Clark.

A Portland native, Lindstrom was the first member of his family to attend college. He paid for his education by working summers at a salmon cannery in Cordova, Alaska. When he transferred to Lewis & Clark, he picked up shifts at the Templeton information desk. “I never had any money, so Mary Potter, who was the secretary working with me at the time, had her eye out for me,” he says. “She would always tell me when there was a lunchtime conference so I could sneak in and get a free lunch. And bless her heart, Mary and her husband, Donald, were at the premiere of Alien Boy.”

At Lewis & Clark, Lindstrom took video and radio production classes taught by Stuart Kaplan, now professor emeritus of communication. “He was extremely interested in the craft and the subject matter of documentaries,” Kaplan says. One moment that Kaplan and Lindstrom both point to as transformative was when Kaplan screened Harvest of Shame, Edward R. Murrow’s documentary on the plight of American migrant farmworkers. “Brian was really captivated by that, and thought that that’s the kind of thing he would like to do,” Kaplan says. “Documentaries that could bring about social change.”

“Stuart took a real interest in me,” Lindstrom says. “After I took that video production class, he gave me a little note that said, ‘I honestly believe that you have the talent and drive to be a filmmaker.’” Along with the note was a gift certificate for a class at the NW Film Center in downtown Portland, where Lindstrom now teaches occasionally. He enrolled in a documentary class and made a 16-mm film about his grandfather and “hiscronies who used to have breakfast at the Newberry’s in Lloyd Center.” He was on his way.

Throughout his career he has strived, in his own words, to “expose some grit and grace, that otherwise you might not know was there, in the people you may walk by every day.”

“It gave me opportunity,” Lindstrom says of Kaplan’s gift, “and it also gave me, in the best sense of the word, an expectation to live up to.”

After graduating from Lewis & Clark, Lindstrom applied (with help from Kaplan) to the film directing program at Columbia University, where he spent five years studying filmmaking and producing educational videos for the New York City Department of Transportation. He made two thesis films —a dramatic short adapted from a Charles Baxter short story and a five-minute documentary about the great schoolyard basketball player Earl “The Goat” Manigault— before returning to Portland. He then started teaching at the NW Film Center and “doing a lot of filmmaker-in-the-community stuff.”

Lindstrom’s community activities included teaching basic filmmaking to the clients of Central City Concern, a Portland nonprofit that provides housing, health care, and addiction-treatment services. In 1999, he completed Kicking, a half-hour documentary that follows three drug addicts through the medically supervised detox process at Central City’s Hooper Detox Center. The film was featured at the Northwest Film & Video Festival and aired on Oregon Public Broadcasting in 2000.

After Kicking, Lindstrom moved from detox to recovery, following the clients of a then-new program at Central City that pairs recovering addicts with mentors who introduce them to drug-free housing and support meetings. “I started basically just showing up with my camera and following people around for months and months at a time,” he says. “It was wonderful, because they were so engaged in what they were doing—they’re really involved in the sacred work of saving lives—and so my presence wasn’t really even noticed that much. I feel so privileged to be allowed in like that, to be given that access and that intimacy.”

When James Chasse died, in 2006, Lindstrom was working on finishing Finding Normal. He didn’t make much of the story at first—“these events whirl around us,” he says—until he was approached by Jason Renaud, a mental health advocate who had worked at Central City Concern during the making of Kicking, and a high school acquaintance of Chasse.

“Jason’s always been a diehard advocate for people with mental illness. When he approached me, he was looking for a way to humanize mental illness, and he felt that a documentary might be an opportunity to do so,” Lindstrom says. “There was this very controversial, upsetting police incident and civil suit that would probably create enough interest that the audience would also be willing to sit with James’s life story.” Lindstrom agreed to make the film. He didn’t suspect he would still be making it six years later.

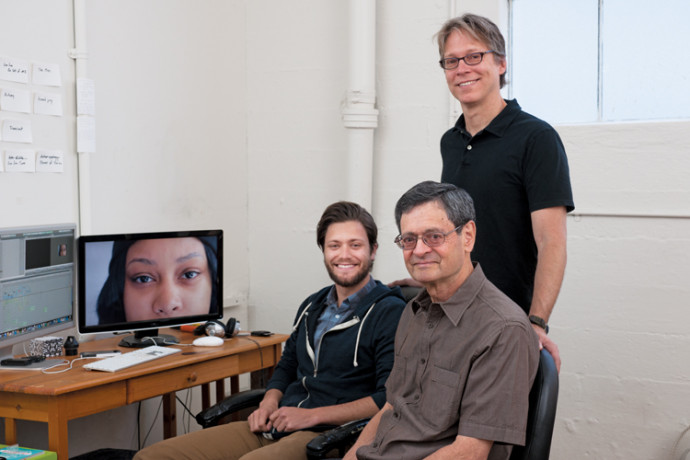

Although the Alien Boy team had plenty of talent—Lindstrom; cinematographer John Campbell, whose credits include Gus Van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho and Mala Noche; and Andrew Saunderson BA ’08, who started as a student intern and wound up credited as editor and coproducer (see related article)—they faced a plethora of legal and logistical obstacles. Chasse’s parents, who filed a wrongful death suit against the City of Portland, couldn’t be interviewed. Many documents relating to Chasse’s death and the Portland Police Bureau’s subsequent internal investigation were kept secret by a judge’s gag order. Among the city attorney’s arguments for extending the order was the fact that Alien Boy was being made.

I started thinking about stories I really wanted to tell, and it seemed like film was the best format to tell them in.Brian Lindstrom BS ’84

Lindstrom and his collaborators kept plugging away regardless. “It was an exercise in faith,” he says. “We would just show up and do the work and hope that a way would be revealed.” It wasn’t until 2010, when the Chasse family received a settlement of $1.6 million from the city, that much of the evidence that appears in the finished film became available.

Lindstrom and Saunderson spent the next 18 months meticulously piecing the film together. “Brian has hyper-attention when it comes to story and character,” Saunderson says. “He’s not afraid to watch the same clip hundreds of times to shave off five frames.” The pair kept track of the film’s scenes with index cards tacked to the wall of their editing room. “I think we probably exhausted every mathematical possibility of how to arrange those cards,” Lindstrom says, but eventually, they got there. Alien Boy was finally finished.

—

Alien Boy’s premiere was a hit. Portland critics described the documentary as “infuriating, tragic, heartbreaking, and incendiary in equal measures” and “an emotional bulldozer.”Charlie Hales, the city’s newly elected mayor, called it “a stunning film.” In February, the film was selected for the Big Sky Documentary Film Festival, and in March it was chosen as an official selection of the Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival.

Today, Lindstrom is focusing on his personal work. He recently gave a TEDx presentation in Portland, and he is researching a potential documentary project on the 1970s singer Judee Sill. He is also spending plenty of time with his two children—a necessity, since his wife, Cheryl Strayed, has spent much of the last year traveling in support of her best-selling memoir, Wild.

Despite the many demands on his time, Lindstrom still finds time to teach. In March, he led a class of students with the “I Have a Dream” Foundation through the creation of a short film about their lives. Watching him coax reticent teens into telling their stories, it’s easy to see what Kaplan means when he says that Lindstrom is “extremely good” at gaining the trust of his interview subjects. He truly seems to be, as Kaplan puts it, “an authentic, passionate person.”

“Teaching is something I do directly as a result of Stuart,” Lindstrom says. “I feel like if I can, in my lifetime, impact one student the way Stuart impacted me, I will have carried on his legacy.” As anyone who watched him at work with the Dream students could tell you, that’s a pretty sure bet.

Ben Waterhouse BA ’06 is a freelance reporter in Portland and communications coordinator for Oregon Humanities.

More L&C Magazine Stories

Lewis & Clark Magazine is located in McAfee on the Undergraduate Campus.

MSC: 19

email magazine@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7970

fax 503-768-7969

The L&C Magazine staff welcomes letters and emails from readers about topics covered in the magazine. Correspondence must include your name and location and may be edited.

Lewis & Clark Magazine

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road MSC 19

Portland OR 97219