From Butte to Cairo: A Daredevil Journey

Open gallery

Pauls Toutonghi, associate professor of English, will dig and delve into everything—cultures, food, slang, even copper—to find the core of a story. Then he’ll dig again.

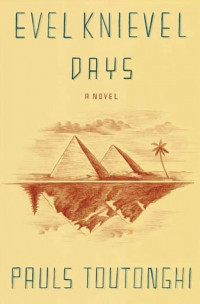

It’s a long journey from Montana to Cairo, both geographically and psychologically, in Pauls Toutonghi’s latest novel, Evel Knievel Days (Crown Publishers, 2012). Driven by a highly likeable, albeit quirky, first-person narrator, Khosi Saqr, the novel traces his search for an absent father, a lost history, and a greater understanding of himself.

Khosi has always felt like an outsider in Butte, Montana, hometown of motorcycle daredevil Evel Knievel. Half Egyptian, he was raised by his single mother in a town where no one could pronounce his name. During Butte’s annual festival, Evel Knievel Days, the girl Khosi has come to love announces she’s about to marry another man. This leads him to take the first daredevil risk of his life: to travel to Egypt to find his father and his identity.

As an author, Toutonghi is at home exploring the interplay of cultures and their impact on character. Born in Seattle to an Egyptian father and a Latvian mother, he grew up hearing a cacophony of languages and ideas at the dining room table. He brings this rich multicultural perspective

to his writing.

“I built Khosi’s character from the city of Cairo,” Toutonghi says. “I knew which version of Cairo I wanted to render— chaotic, overwhelming, and loud. This helped me define Khosi as an outsider whose personality was in opposition to this reality. From there, my job was to write him toward this new direction, which I enjoyed doing.”

Toutonghi determined early on that Cairo would be Khosi’s destination, but he still needed an initial setting for his novel. After some consideration and plotting, he chose Butte, a town he had previously researched for a separate project. “Butte is both fascinating and fractured. A century ago it was a copper mining powerhouse. Today, you see the evidence of the type of destruction that comes with that industry. It was important to get both of these realities into the book.”

Setting the novel in the present day, Toutonghi realized the world in which the story was coalescing was in a state of upheaval. This awareness affected his approach to the final few chapters, as well as revisions to the novel’s overall structure.

“The novel is set in 2008. I was literally shaping the narrative during a visit to Cairo in 2011, while the revolution was happening. For a book that’s partially set in contemporary Egypt, there had to be at least an allusion to the revolution. Otherwise, I’d miss the mark. As far as Khosi is concerned, to go from the obsessive young man we meet in Butte to the one who becomes comfortable in a frenetic metropolis in the midst of a revolution … you can’t have a more complete transformation than that.”

As a writer and a teacher of writing, Toutonghi still finds revision to be the most daunting—and rewarding—part of the work.

“It’s is the hardest thing to learn. You have to think from the ground up, and try to divorce yourself from some of your story’s emotional content.” For Toutonghi, this could mean deleting pages of dialogue, cutting a character, or retrofitting a story’s entire framework if necessary.

“One of my earliest short stories required six versions, and that came after the magazine accepted it. It can be tiring and grueling, and it’s easy to lose faith. But you have to stay with it.” Toutonghi writes at a wireless keyboard and sits where he can’t see the monitor, all in effort to disable his inner critic. He brings this awareness

of the constant negotiation between writer and editor into his writing and teaching.

“I try to explain to students what’s involved in the writing life. The best anyone can say is, ‘Here, go in this direction. I’m not sure what will happen, but just go.’ I’ve worked with some talented writers looking for the way forward. To help them, even when the odds are long, is a privilege.”

—by David Jarecki

More L&C Magazine Stories

Lewis & Clark Magazine is located in McAfee on the Undergraduate Campus.

MSC: 19

email magazine@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7970

fax 503-768-7969

The L&C Magazine staff welcomes letters and emails from readers about topics covered in the magazine. Correspondence must include your name and location and may be edited.

Lewis & Clark Magazine

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road MSC 19

Portland OR 97219