William Stafford symposium meets with success

Open gallery

by Sara Balsom BA ’14

On Saturday, March 15, the William Stafford Centennial took up where it left off after the February 7 tribute to William Stafford at the Newmark Theatre. Despite a blitz of inclement weather that fell over Portland on the weekend of the 7th, the Newmark event was still attended by about 300 guests, and the rest of the symposium—rescheduled to March—survived mostly intact.

Scholar Fred Marchant was one of the speakers missed at the symposium but able to attend the Newmark celebration. Most bus lines were closed and roads were choked with snow, still several hundred people made it to the reading downtown. As Professor Jerry Harp later remarked, “There was a feeling that we were the intrepid few who couldn’t be stopped from coming to the reading. It was a convivial evening created by that sense that we had come out in defiance of the conditions [to join] in something together.”

Matthew Dickman introduced the poets Mary Szybist, Tony Hogland, and Li-Young Lee; and Kim Stafford moderated a dialogue between Hogland and Lee about Stafford’s poetry. In between these speakers, film and photographs of Stafford made the event a multimedia experience. One reel of footage showed Stafford speaking on a panel of poets, including Richard Eberhart and Anthony Hecht, about the relationship between poetry and politics. In the clip, Stafford expresses shock and dismay when one speaker remarks that “good poetry is not political.”

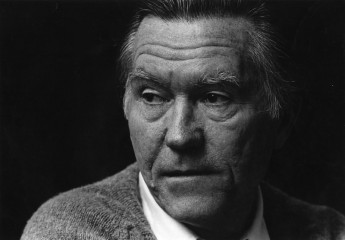

The rescheduled symposium, “You Must Revise Your Life: Stafford at 100, A Celebration and Reassessment,” took place on Saturday, March 15, and gathered together people who knew Stafford firsthand, archivists who knew him through his writing, and others who were introduced to him perhaps for the first time on Saturday. The day-long event was composed of several panels and a self-guided tour of the Stafford exhibits in Watzek Library and the Hoffman Gallery. Someone who had never encountered Stafford before could glean a sense of his person, ethics, writing habits, and character. This portrait of Stafford is one of a humble, talented, and hardworking teacher, poet and family man—someone dedicated to the craft of writing, to “concentric peace,” and to human connection.

Kimberly King BA ’75, a former student of Stafford’s, recalled the deep respect he showed to all his students, citing a comment he had left on one of her assignments: “I’m copying into my notes your comments on the first page.” King remarked, “He wanted to be able to go back to what I had written and reflect on it at length; what a deep level of respect that shows.”

Stafford practiced teaching with an egalitarian approach and unassuming consideration of his students’ ideas. He asked students to “master language by using it [and] not write just to please the teacher.”

Primus St. John, another former student, recalled the nature of Stafford’s responses to students: “When he was critical [of a student’s thought]—it was rare—he would say, ‘I’d never thought about that before. Maybe if you looked at it again another way you might see it a little differently, but I like your idea a lot.’”

From their recollections it seems that Stafford didn’t push writing and literature on his students, that he instead helped them “draw on [their] inner reserves,” to find the writing and the love for literature that they already possessed.

In Kim Stafford’s opening speech, he quoted Basho, saying “Don’t seek the old masters, seek what they sought.” The Stafford symposium was a day dedicated to seeking what William Stafford sought and a reminder that when we try to urgently seek somebody we can lose ourselves in a world of perceptions.

A well known anecdote was told during the first Q&A session about when someone at a reading had called out to Stafford, “I could have written that!” Stafford’s response was recounted by two audience members: “‘Yes, but you didn’t,’ is what he said,” the woman telling the story laughed. A man piped up from the front row, “Well, I heard it a little differently, what he said was, ‘But you could write your own.’” They quickly agreed he had said both things. It became clear from that moment that we had gathered together not just to sift through a life, asking who was he? But to draw on our inner reserves, to remember how he did what he did, the people with whom he made connections, and what he saw in others.

“I remember…” was said to be one of Stafford’s favorite writing prompts. He told students to think of something they had done but to write what they might have done. “You must revise your life,” he is famously quoted as saying. Revision and reimagining were both part of Saturday’s symposium, an event revised in its own way due to weather conditions and dedicated to imagining and reimagining Stafford.

The Stafford symposium was a time to remember someone and also to ask what it means to remember. At the end of the day, I wanted to know the man described by his son as “strewing beauty, curiosity, and connection,” the poet who relied on “concentric peace,” and the professor who asked his students to draw on their inner reserves. And I realized the best way to know Stafford would be to seek these things for myself.

“When we don’t know something, we are given the best chance to understand poetry. When we think we know everything, we are blind,” Kim Stafford quoted his father as saying.

I held this thought in my head as I left the symposium. I considered what I now knew of this man I had never met—the photographs, video clips, his voice resonating through the chapel from a recording. I can’t pretend to know him now. But I was given the chance, that day, to imagine who he might have been.

A version of this article originally appeared in Wordsworth, the English department newsletter.

More Newsroom Stories

Public Relations is located in McAfee on the Undergraduate Campus.

MSC: 19

email public@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7970

Public Relations

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road MSC 19

Portland OR 97219