Decades of Distinction

Michael Ford and Vern Jones, two pillars of the Lewis & Clark community, retire.

Open gallery

Last spring, two pillars of the Lewis & Clark community retired after each serving roughly four decades. It’s not an exaggeration to say Michael Ford and Vern Jones influenced generations of students, leaving behind legacies that have shaped both the undergraduate college and the graduate school.

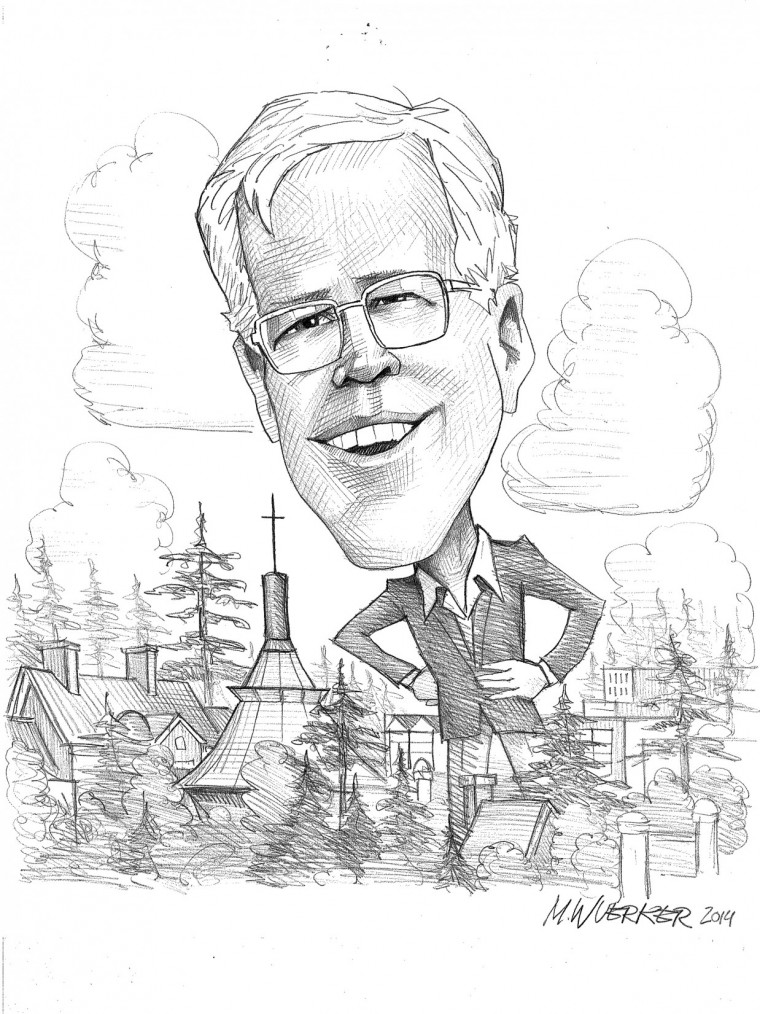

Michael Ford

Associate Vice President for Campus Life

Years of Service: 38

Michael Ford joined Lewis & Clark as director of student activities/assistant to the vice president for student life in 1976. During his influential career at the college, he as served as director of student activities; director of campus programs; director of alumni relations; director of annual giving; director of campus life; dean of students; and, most recently, associate vice president for campus life.

Career arc—My career is very unusual because I’ve held so many different positions at one school. I’ve never had a day when I haven’t enjoyed my work, and I’ve never had a day when I haven’t been challenged.

I’ve worked with students, faculty, alumni, parents, and trustees. I’ve worked for five presidents and several interim presidents. My role here has always been to collaborate and to help create, sustain, and renew. Sometimes I nudge and prod, sometimes I ask questions that aren’t particularly pleasant for people to hear, but I try to act diplomatically, and I try to always do it in a context of continuous community improvement.

Creation of SAAB—Students in the early 1980s started the Student Academic Affairs Board, or SAAB. They started it because student government wasn’t working very well for them. All I did was ask a question, “Why are you here?” They said, “We’re here for the academic life of the college.” I said, “Well, you have a student government [based on campus housing assignments] that’s out of alignment with that.” It didn’t take them long to come up with SAAB, a solution that aligned part of student government with the academic structure.

SAAB is still thriving today, funding student research initiatives and other academic expenses via a board of student representatives from each academic discipline. Over the last 30 years, SAAB has given out more than 1,000 grants and over $1 million. There are lots of schools that have faculty who can garner resources and hire students for their research projects. But SAAB flips that idea on its head and asks, “As a student, what’s your idea? What do you want to work on?” Students evaluate each project and make a funding decision. And it’s all backed by student fees. To our knowledge, no other school does it.

I’m very proud of SAAB. We’re currently working on a 30-year video history of the program because it says a great deal about what matters to our students here.

Origins of College Outdoors—College Outdoors started because an outdoor entrepreneur, Wayne Haack, walked into my office and said, “Why do you have a climbing club but no outdoor program? You’ve got all this outdoors stuff you’re not doing.” So he and I initiated College Outdoors, working with students from the outset. After several years with part-tme staff, the college hired a full-time director, Joe Yuska.He been running the program for the last 25 years.

Today, College Outdoors is extraordinary: more than 100 trips a year, trips before orientation, stuff at spring break—none of that would have been possible without initiative, renewal, and the work of lots of people sustaining it over time.

Community standards—One of my most important legacies relates to community standards. I’m particularly proud of the work I did as dean of students with regard to the Student Code of Conduct, which was initiated in 1994. I worked closely with students to craft and annually revise the code, hire and train residence hall staff, re-energize a Student Peer Review Board, and address the challenging issue of academic dishonesty. I also served as the staff facilitator for the creation of the college’s Academic Integrity Policy and College Honor Board, both of which remain in place to this day.

In recent years, I’ve played a key role in centralizing the college’s event management operations, facility-use priorities, and cocurricular activity scheduling.

And along the way, I’ve coordinated several iterations of the college’s cultural arts series, multiple special events with academic departments and student groups, 18 commencements, and two presidential inauguration ceremonies. In 1992, I was priileged to coordinate the largest participatory event in the college’s history, the Chairman’s Challenge (a.k.a. “Beat Bob”). Thousands of our community members participated in a daylong series of physical fitness events, which resulted in a major gift for Watzek Library from then–board chair Dr. Robert B. Pamplin Jr.

What makes Lewis & Clark tick—What I’ve seen is a substantial history of ongoing creativity, initiation, and collaboration. We always build on what came before. All you have to do is take a look at the lectureships, the symposia, and notice the word “annual.” Somebody had to start all those—often students in collaboration with faculty. Those programs and events didn’t just happen—they became realities because of a lot of hard work along the way. You can’t ever take that for granted. You have to create an environment that says to people, “You can own this place, this place is designed for you to make a difference.” Then you do everything you can as a staff or faculty member to help draw students out so that they can be educated in the arts and sciences—so that they can, indeed, make a difference.

To honor Michael Ford’s legacy, the Michael and Mary Lynn Ford Scholarship fund has been established to benefit future generations of Lewis & Clark students. To make a gift to the fund, visit go.lclark.edu/give/now/ford.

Vern Jones BA ’68

Professor of Teacher Education

Years of Service: 41

Vern Jones BA ’68 has been a junior high school teacher, a junior high school vice principal, and a district resource coordinator for students with emotional and behavior disorders. But many members of the Lewis & Clark community know him best as a longtime professor of teacher education in the Graduate School of Education and Counseling. A national expert in classroom management and student behavioral disorders, Jones has written a number of authoritative textbooks in his fields of expertise and has consulted with schools in more than 25 states.

Path to Lewis & Clark—I originally came to Lewis & Clark as an undergraduate student in the mid-1960s. I was running track and field, and Eldon Fix was a renowned coach at the time. He was one of the main reasons I came to Lewis & Clark.

In college, I was kind of a nerd. I majored in sociology, minored in English, and took a number of psychology courses. All I did was study and run, and run and study. My folks were in Texas, so Eldon became my surrogate father and the track team became my brothers. Immediately after graduating from Lewis & Clark, I was awarded a scholarship to earn my doctorate in counseling psychology from the University of Texas at Austin.

Areas of expertise—For 44 years, I was able to do something that I love, that I was pretty good at, and that seemed to make a difference in the world. First and foremost, I was committed to being a teacher. I think my students have left Lewis & Clark more skilled and better able to help a wide range of students experience school success. Second, I think I’ve been a real support for my colleagues. Among other roles, I’ve been associate dean of the graduate school, chair of the teacher education program, and director of the doctoral program. I’ve also enjoyed helping junior faculty move their careers forward. Third, I think the college’s reputation has benefited from my large number of publications and presentations—particularly in the fields of classroom management and behavior disorders. But I would put that third because I think that students and faculty come first and second by a mile.

Birth of the graduate school—In 1983, I chaired a planning committee that recommended we consolidate the college’s diverse graduate programs into a graduate school. The following year the Board of Trustees approved the idea.

In 1985, I received a large grant from the U.S. Office of Educational Research and Improvement to review best practices for teacher education. We were one of 11 schools in the country—and the only liberal arts college—to receive the grant. We studied best practices for three years with teams of faculty, public school teachers and administrators, and teacher education students. In the end, we identified three key elements: teacher education needs to happen at the graduate level; it needs to be organized using the cohort model, in which a group of students moves through the program together; and students need to be involved in a full-year internship/student teaching experience.

Prospective teachers should get a strong liberal arts background and then they should learn how to teach. When you mix the two at the undergraduate level, you get only half of each. Teachers need to take high-quality professional courses like a doctor or a lawyer or anybody else. That’s why we created a master’s level program at the graduate school—and it’s still in place today.

During the graduate school’s first few years, faculty were housed in several different buildings on the undergraduate campus. In 2000, Lewis & Clark purchased the Franciscan Renewal Center from the college’s neighbors, the Sisters of St. Francis. Once the graduate school moved into Rogers Hall on south campus, it allowed the faculty to spend more time together and to use our expertise collaboratively across programs.

Long-term motivation—Over the years, I’ve had the opportunity to work with incredible students. People graduate from Lewis & Clark and become change agents. It’s intentional on our part. We teach to it. We want people to see what needs to be changed. We want them to be excited about making schools better places for students, and we believe this energy and excitement will enable them to make full use of their talents and not burn out.

Desired legacy—I hope my students take away a sense that all children can be successful, all children want to be successful, and their parents want them to be successful.

Instead of thinking in terms of discipline, behavior problems, or skills deficits, we need to think about environmental mismatches. We need to realize that we have control over a wide range of variables in schools and that we can create environments where virtually all students can succeed both behaviorally and academically. When we believe this, it changes the way we look at students and their education. I think it empowers educators, and I believe this, in turn, enables them to empower their students.

More L&C Magazine Stories

Lewis & Clark Magazine is located in McAfee on the Undergraduate Campus.

MSC: 19

email magazine@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7970

fax 503-768-7969

The L&C Magazine staff welcomes letters and emails from readers about topics covered in the magazine. Correspondence must include your name and location and may be edited.

Lewis & Clark Magazine

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road MSC 19

Portland OR 97219