Why should planet Earth care about (non-planet) Pluto?

Open gallery

by Ethan Siegel, PhD

In 1930, more than 80 years since the discovery of Neptune, a young astronomer from Kansas named Clyde Tombaugh scanned the sky for Planet X.

There wasn’t a compelling reason to think there’d be another world beyond Neptune, but there was no good reason to think there wouldn’t be. In the interest of knowledge, curiosity, and science, he took up the search.

Tombaugh used a novel technique: he would photograph the same region of sky on two different nights and scour the two images for any lights that appeared to be in different locations. While stars are at such great distances that even the fast-moving ones will appear to be in the same position, any bodies within our solar system should show themselves. Images of a star-filled patch of sky on January 23 and January 29 showed a single, faint light that had moved, a light that was confirmed to be an object beyond Neptune: Pluto.

Though Pluto was initially hailed as the ninth planet, scientists soon realized it was far different from all the other worlds in a number of important ways:

- It was very small—smaller even than Mercury.

- Its orbit was very inclined, orbiting out of plane vis-à-vis the other planets.

- And its orbit was far from circular, with its closest approach bringing it inside Neptune’s orbit, while its greatest distance from the Sun was nearly twice that.

For 48 years, Pluto was the only known object in the solar system past Neptune. When the second one was finally discovered, it was a giant moon of Pluto: Charon. But things began to change in the 1990s. Our technology had improved to the point where other comparably large objects beyond Neptune began to be discovered: Eris, Makemake, Haumea, Sedna, Quaoar, and others, with Eris perhaps even outsizing Pluto. Clearly, Pluto was part of this class of objects—trans-Neptunian objects—distinct from the other eight planets. In 2006, the International Astronomical Union defined what it means to be a “planet” for the first time, excluding Pluto.

Just months prior to that demotion, however, NASA had launched a mission to explore that outer world: the New Horizons spacecraft. You might wonder why it would be important to explore a world that was about to experience such an indignity, but Pluto holds some tremendous keys to our own existence that we often take for granted.

Moreover, studies of the galaxy have taught us that Pluto-like worlds are at least hundreds of times as common as Earth-like ones, meaning that if we want to understand what most of the planets in the universe are like, Pluto is the place to start.

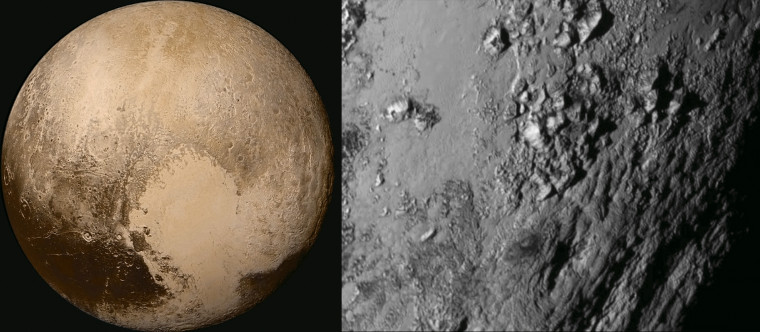

On July 14, the New Horizons mission made its closest approach to Pluto, with all of its instruments functioning properly. While it will take a full 16 months for all the data to come back to Earth (thanks to the nearly 3-billion-mile journey), we’ve already learned some amazing things:

- Pluto has “ice mountains” that are over 11,000 feet tall.

- Its surface has almost no craters, hinting that icy eruptions are common on this world.

- Pluto is covered not just in water ice, dry ice, and frozen methane, but solid nitrogen!

So far, we’ve learned that worlds beyond Neptune are probably responsible for the most abundant gas in our atmosphere, possibly created our oceans, and maybe even provided the building blocks of life. Pluto may yet be found to house geysers, volcanoes, weather, or even snow, but one thing’s for certain: the more we learn about these distant, primitive worlds, the better we’ll understand exactly how our planet, teeming with life, came to be this way.

Astrophysicist Ethan Siegel teaches physics and astronomy at Lewis & Clark College. He has won numerous awards for science writing since 2008 for his blog, “Starts With a Bang,” and also contributes to Forbes and NASA’s “The Space Place.” His first book, Beyond the Galaxy: How Humanity Looked Beyond Our Milky Way and Discovered the Entire Universe, will be published this fall by World Scientific.

More L&C Magazine Stories

Lewis & Clark Magazine is located in McAfee on the Undergraduate Campus.

MSC: 19

email magazine@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7970

fax 503-768-7969

The L&C Magazine staff welcomes letters and emails from readers about topics covered in the magazine. Correspondence must include your name and location and may be edited.

Lewis & Clark Magazine

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road MSC 19

Portland OR 97219