William Stafford Archive fosters education on campus and beyond

Open gallery

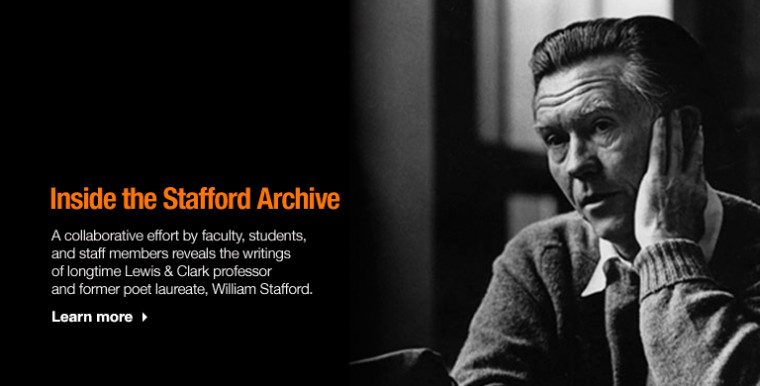

A tremendous collaboration underway at Lewis & Clark is producing a collection of invaluable resources for educators, authors, historians, and fans of one of America’s foremost poets. Since the William Stafford Archive arrived at Lewis & Clark in 2008, a dedicated team of staff members, students, and faculty have been hard at work to harness the full potential of the archive as a vital tool for instruction on campus, in the Portland community, and beyond.

The family of William Stafford generously donated the archive to Lewis & Clark, enabling the college to share the renowned poet’s work with a new generation. Stafford, who passed away in 1993, was Oregon’s poet laureate from 1975 to 1989 and a professor at Lewis & Clark for more than 30 years.

The archive contains an incomparable range of materials, including Stafford’s daily writings, correspondence, photographs, recordings, and teaching materials.

“The compelling story of the William Stafford Archive is, I think, the poet’s awareness of the importance of preserving the record of a complete poetic life,” said Paul Merchant, William Stafford archivist and special collections associate. “The archive may be unique in its comprehensiveness. We certainly intend to provide unprecedented access to its content, with finding aids and digitized files at an unusual level of detail.”

Collaboration moves the archive forward

Though Stafford published more than 50 books in his lifetime, the disciplined daily writer also kept a complete record of his daily writing and of revisions to his work. Over the course of 40 years, he accumulated more than 20,000 pages of daily writings, as well as a large collection of correspondence and many thousands of photographs he took of fellow poets, family, friends, and Lewis & Clark College faculty.

The size and scope of the archive offers a fuller record of the poet’s life than comparable collections by other authors, promising to present unparalleled opportunities for research and instruction.

“The completeness of the archive sets this project apart because there aren’t other representations of this kind of work out there,” said Doug Erickson, head of special collections. “Bill’s dedication to writing every day and keeping his work organized has made our work with the archive possible. This project now stands as a significant example of what can happen for literary archives when so much is available.”

Lewis & Clark students working with the archive have been gaining firsthand experience in the essentials of biographical and archival processes. In the past year, twelve students have contributed to archive projects, some as paid student workers and some as volunteers.

“Students in the English and history departments, in particular, have been working within the archives,” Erickson said. “For their involvement, many of these students earn academic credit. Perhaps more importantly, though, students gain valuable hands-on experiences that—at another institution—might be reserved for graduate students.”

As students work on the front lines of the digitization process, a team of staff members from special collections and Watzek Library has sought innovative solutions to organize and display the archive in a user-friendly way.

“We didn’t have a formula to follow,” Erickson said. “We couldn’t say, ‘Let’s just do what they did with the Emily Dickinson archive,’ because nothing like the Stafford archive exists elsewhere. This is truly a unique project, which has lent itself to the imagination of our staff. We were starting from scratch in designing the website, relying on the ingenuity and creativity of our staff.”

Visitors to the William Stafford Archive website will see the impressive results of the team’s efforts. To date, students and staff have digitized Stafford’s first two books of poetry, West of Your City (1960) and Traveling through the Dark (1962). For each collection, visitors can view the drafts and typescripts of poems, alongside supplemental audio and video material, when available.

The poem “In Dear Detail, by Ideal Light” exemplifies the archive’s extensiveness; Stafford wrote and revised the poem over the course of two months in 1958, and more than 20 versions appear on the site.

“In some instances we see him wrestle with the words and a poem slowly emerges,” Merchant said. “Most days, though, you see Bill’s natural gift for poetry, where beautiful poems spill out in journal entries left with barely a correction. His sustained daily writing habits tuned his mind for such creation.”

Stafford’s most famous poem, “Traveling through the Dark,” appeared in his daily writing in June 1956 in its nearly complete form.

The materials currently available on the archive website represent just a portion of the entire collection. In coming years, an updated bibliography of William Stafford’s work should become available, stemming from a collaboration between the Special Collections staff and Joanna Haney, coordinator of research services for Watzek Library. The new bibliography will entirely upgrade the partial Stafford bibliography by the late James Pirie, former Watzek librarian. When it comes online, the bibliography will provide the key to the entire collection, linking to texts and related visual and spoken materials.

This year, archivists are working to finish digitization of Stafford’s daily writings and to complete a catalog of all of Stafford’s correspondence, which will appear online. The catalog will offer a finding aid for anyone interested in learning more about Stafford’s relationships with other poets. Archivists are also beginning their work with Stafford’s extensive collection of photos and negatives, as well as the many audio and video recordings of Stafford reading his poetry.

“We originally intended our work with the Stafford archive to take five years,” Erickson said. “By all indications, we’re ahead of that goal. We can’t overemphasize the help students have provided in this project.”

The archive as a teaching tool

In addition to the hands-on work being done with the archive, Stafford’s work is beginning to reach wider audiences through an educational initiative taken up in tandem with the archive.

Kim Stafford, William Stafford’s son and literary executor, has overseen the process of developing and collecting resources for teachers. Director of Lewis & Clark’s Northwest Writing Institute, he worked last summer with two William Stafford Writing Fellows, Sara Guest and Jeff Coleman, to facilitate a workshop for area teachers to create curricula around William Stafford’s poetry. As a result, teachers created and honed a series of resources for primary and secondary classrooms.

The resources, which are now available on the William Stafford Archives website, provide suggestions for lesson plans, discussion topics, and writing assignments focused on selected portions of the archive, representing themes in Stafford’s writing, like the environment, and writerly concerns, like editing.

“The curricula created by the teachers in the House of Words project, offering units designed to be used at every level from grade school to high school seniors, are now posted on our William Stafford Archives web page. The presentations by three of the teachers, well described by Jeff Baker in his recent Oregonian profile, gave an inspiring insight into the classroom use of Stafford’s poems,” Merchant said.

Though local educators have access to the tangible materials in the archive, digital materials and teacher resources are available on the website for visitors to access from anywhere. The public’s unprecedented access to the poet’s archive will ensure that Stafford’s legacy will continue for generations to come.

“There is great potential for further work by teachers in developing curriculum for teaching writing, literature, peace-making, sense of place, and other topics using the resources of the William Stafford Archive,” Kim Stafford said. “We are in discussion about how to continue his work.”

Documentary demonstrates Stafford’s important legacy

In addition to his work as a poet and an educator, Stafford is renowned for his pacifism. Stafford was drafted to fight in WWII, but registered as a conscientious objector and worked in the Civilian Public Service camps on forest and soil conservation from 1942 to 1946. His commitment to pacifism, nature, and human community would serve as guiding themes in his writing throughout his life.

“For William Stafford, the practice of writing and the life of witness were a single project,” Kim Stafford said. “When my father got up before dawn to write, he was beginning his engagement with a world at war. As a writer, teacher, and witness, he sought reconciliation with the self, other people, and the earth. His writing holds out to us the possibility of friendship in all directions.”

In 2003, Kim Stafford edited the book Every War Has Two Losers: William Stafford on Peace and War, which collected the lifelong pacifist’s antiwar writings. Last year, a documentary based on the book appeared, featuring readings by Alice Walker, Maxine Hong Kingston, Naomi Shihab Nye, Coleman Barks, Michael Meade, W.S. Merwin, and others. Kim Stafford served as associate producer for the film, which examines the history of violence through war, and alternatives to war through language, personal witness, and cultural engagement.

Lewis & Clark will host a special public screening of the documentary Every War Has Two Losers on February 25 at 12 p.m. Kim Stafford will offer an introduction to the film and host a conversation following the screening.

More Newsroom Stories

Public Relations is located in McAfee on the Undergraduate Campus.

MSC: 19

email public@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7970

Public Relations

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road MSC 19

Portland OR 97219