Abroad in Hungary: Student or Spy?

by Benjamin Ostrom BA ’85

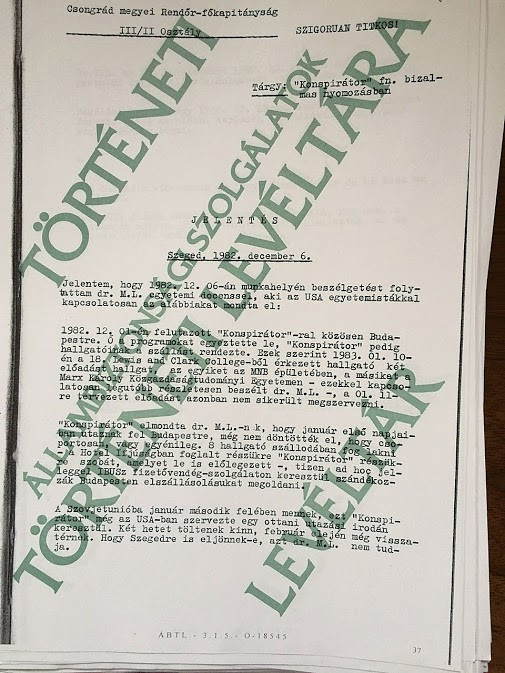

The reports arrived from Hungary in a dusty envelope topped with colorful stamps. Inside, each document was labeled “Top Secret” and imprinted with the green watermark of the National Archives in Budapest.Open gallery

by Benjamin Ostrom BA ’85

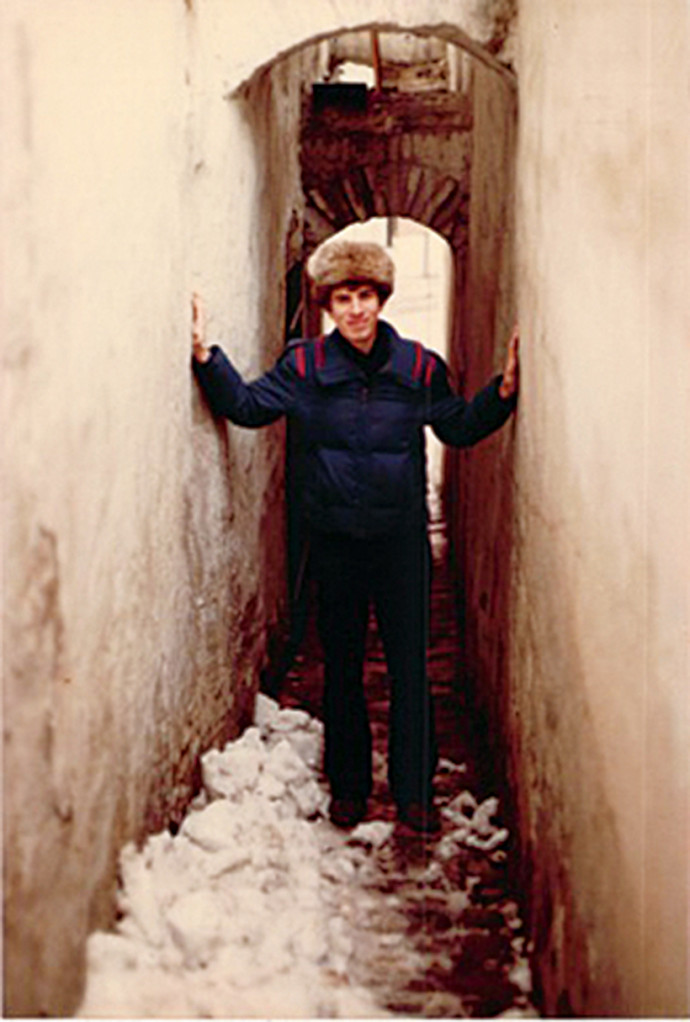

The reports arrived from Hungary in a dusty envelope topped with colorful stamps. Inside, each document was labeled “Top Secret” and imprinted with the green watermark of the National Archives in Budapest. Quite by accident, I held in my hands my 89-page Hungarian secret police file—compiled unbeknownst to me during my Lewis & Clark overseas study program to Hungary in 1982–83.

“We have approximately 1 ½ hour to conclude the search. Agent “Krisztina” will be present as a guest at Hagi restaurant. At 7:30 she will use the restaurant’s public telephone to call 14-003, where Dr. Laszlo Foldvari, police sergeant, will be on call. “Krisztina” will indicate that all the students have arrived with the coded sentence: “I feel fine, I will stay for about one and a half hour… .”

I was stunned reading this material. Apparently, it was acquired as part of a Hungarian secret police plan to search and photograph diaries and journals of all the visiting Lewis & Clark students. The search described above took place during our farewell dinner. Postcommunist law allows any citizen or resident to request a copy of his or her secret police files. My wife, Edit, eventually did so being a Hungarian national and curious because she had traveled abroad as a student in those days. Later, when checking on her request, we discovered that the Hungarian National Archives had nothing on her but “quite a file” on me. So I, too, submitted a request in 2012 and received the package in 2013. My wife translated it over the next six months as time allowed.

The informants to the secret police were Hungarian faculty members and some students, all with code names such as “Krisztina”(who, it turns out, was our group’s Hungarian teacher), “Celtic,” “Ilku,” “Rodostoi,” “Piko,” and “Szaloky.” Interviews with police took place at a secret apartment with the code name “Sztar.” Reports were also made from Budapest, when our group visited Karl Marx University and the National Bank. The Hotel Ifjusag in Budapest was also searched and about 200 photocopies of diaries and journals were taken. Six bugs had also been planted. All of this information was sent to the Ministry of Interior.

The striking part of reading this over 30 years later is that the reports try to weave a storyline, the main premise being that our group’s leader, Marty Hart-Landberg, professor of economics, and his wife, Sylvia, were the “conspirators” who “assigned” students to gather information. I was supposedly assigned the Hungarian military as a topic.

The irony is that our group was very inquisitive, and, yes, we were assigned homework (talk about mirror-image theory). Being 19 years old at the time, I probably did ask questions such as ”What do the Hungarian people think of the Soviet army presence?” and “How does the Hungarian public relate to the 1956 events?” But it was interpreted differently as exemplified in one report—“Analysis: The information qualifies as valuable proof of surveillance activity. This proves the fact that USA nationals studying or staying in Hungary are supplied specific tasks.”

Often facts were distorted or filled in to make them coherent. Many names were misspelled. The student informants were typically very coy and did not offer much material. On the other hand, some faculty added embellishments, and these anecdotes were quite funny. At the time, being a Hungarian professor was very prestigious and provided a lot of benefits (such as travel to the West), but it also meant being willing to serve as a government informant, if required. This was particularly true for those associated with English-speaking students. Some were paid to inform as well.

In an unwitting “hat’s off” to Lewis & Clark’s overseas study programs, one of the last reports states: “It is evident that the Americans gained significant knowledge of the country by visiting various cities and regions. They traveled to neighboring socialist countries with the same objective. It was very easy for them to make contacts during their travels, and they gained up-to-date information about the political situation from these conversations.”

According to the file, the Ministry of Interior closed the criminal case on March 30, 1983. It is comforting to know that my group had left the country safely by then after having had a delightful and life-changing overseas experience. Little did we know we would be reading about our brush with espionage 30 years later.

More L&C Magazine Stories

Lewis & Clark Magazine is located in McAfee on the Undergraduate Campus.

MSC: 19

email magazine@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7970

fax 503-768-7969

The L&C Magazine staff welcomes letters and emails from readers about topics covered in the magazine. Correspondence must include your name and location and may be edited.

Lewis & Clark Magazine

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road MSC 19

Portland OR 97219