With a Picket Sign in My Hands

I remember the Lewis & Clark campus of the late 1960s as a collection of terracotta brick, grayish stone, and brownish wood buildings, all of which were nestled in acres of seemingly endless green.

Open gallery

by Marti Arnold Alston ’69

I remember the Lewis & Clark campus of the late 1960s as a collection of terracotta brick, grayish stone, and brownish wood buildings, all of which were nestled in acres of seemingly endless green. Despite its Portland address, the College was tucked in an area that bore more resemblance to a park than to a large metropolitan area. Back then, we students had long hair and wore turtlenecks and jeans. We had a palpable desire to make a difference in the world. It seemed part of the very air we breathed.

The Detroit to which I came three months later could not have differed more from the idyllic college landscape. The neighborhood into which I ventured was the epitome of urban decay. On either side of the streets, pockmarked with potholes, were flimsy homes that had been hastily built for the influx of workers who had migrated to Detroit from the South, Appalachia, and Europe during the early decades of the 20th century. They sought work in the auto plants, at the $5-a-day rate promised by auto magnate Henry Ford. Sprinkled among the houses were mom-and-pop grocery stores and junkyards, whose contents were deemed more valuable than the people living beside them.

The young men of the neighborhood joked bitterly that the juvenile detention center–built at the northern end of the community–was put there to remind them that they had better keep an eye out for the “Big 4,” teams of burly white cops who were just waiting for a chance to inflict street justice on the African American populace.

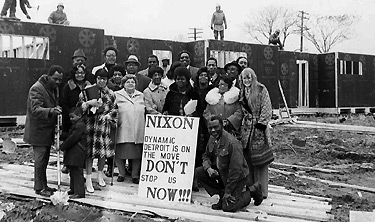

That the community was called “Forest Park” was proof that a city official with a mean sense of humor had named the area. The conditions were so bad, the local newspapers had labeled the neighborhood “Detroit’s Worst Slum.” But for me, Forest Park was an area filled with the energy of people who were fed up with the abysmal conditions in which they were forced to live. Under the leadership of their charismatic leader, Chris Alston–the man I was later to marry and then lose to illness–the residents were ready to challenge the government bureaucrats and transform their neighborhood so that it might one day live up to its name.

Armed with my degree, and an enormous desire to be involved in change-making activities, I snuggled into the human warmth and stubborn commitment that defined Forest Park. The College had prepared me well for this flight into the unknown, this cauldron of despair and hope. Lewis & Clark had taught me to love crawling inside the skin of people from different races and backgrounds when it sent me to France as part of an overseas study program. I had been a complete stranger from another culture–and from a country involved in an unpopular war–yet I was warmly welcomed.

Lewis & Clark had also allowed me to develop my own work-study opportunities. I worked in a home for adolescent girls in France as well as an inner-city school and a church-sponsored community service center in Portland–all within a mere four years.

Thanks to our wonderful school, I experienced the exquisite pleasure of doing the hard but satisfying work of uncovering what was really important to poor and working people–being able to buy their own homes, nurture close ties with their neighbors, keep each other safe, educate their children, and fight city hall to get what they needed.

As part of the handful of Lewis & Clark students who took part in antiwar activities, I knew about standing up to government. On the streets of Portland, I learned to respect the power of group protests. So it was with pride that I joined with the people of Forest Park when my husband suggested we carry our “Save Forest Park” signs into Detroit City Council meetings or stage sit-ins at the city housing offices to assure the release of federal urban renewal money that would rebuild our community.

Lewis & Clark College taught me to hear that hum that vibrates through my body when my beliefs and actions are in perfect alignment. It is the sound that guided me when I was young. It is the sound that will guide me as I move into old age–no doubt, with a picket sign in my hands.

The Chronicle staff welcomes submissions for the back-page essay from alumni, faculty, students, and friends of the College. For more information, call 503-768-7970 or e-mail chron@lclark.edu.

More L&C Magazine Stories

Lewis & Clark Magazine is located in McAfee on the Undergraduate Campus.

MSC: 19

email magazine@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7970

fax 503-768-7969

The L&C Magazine staff welcomes letters and emails from readers about topics covered in the magazine. Correspondence must include your name and location and may be edited.

Lewis & Clark Magazine

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road MSC 19

Portland OR 97219