For Better or for Worse

Lewis & Clark researchers explore earlier views of marriage and gender.

When George Bush called marriage “a sacred institution and the foundation of society” in his 2005 State of the Union address, Katja Altpeter-Jones’ ears perked up. To Altpeter-Jones, assistant professor of German, the president’s words might have been lifted “straight out of a 16th-century Protestant pamphlet.”

Indeed, both then and now, people wrestled with evolving conceptions of marriage and its cultural significance. “Our notions about society and the individual’s relationship to the state, our religious beliefs, and our modern ideas of romantic love together determine how we understand the function and role of marriage today,” says Altpeter- Jones. “In the 16th century and today, marriage provides one of the key models for imagining what a properly ordered society should look like.”

Altpeter-Jones’ research focuses on one overlooked aspect of marriage during those earlier times: depictions of marital violence in popular literature. She hopes her work, which has been aided by Tara Daystar ’06, illuminates not only what 15th- and 16th- century Germans thought about marriage and gender, but also our present-day beliefs.

“Studying earlier times,” says Altpeter- Jones, “has a way of letting you see today’s situation in a very different light.”

In late 15th- and 16th-century Germany, secular and religious authorities were intent on configuring earthly society to match what they believed to be God’s divine order. One result of the Protestant Reformation was a new emphasis on marriage: Priests could wed, marital courts were established, and divorce became possible. Protestants and Catholics alike latched onto the idea that marriage could function as a guarantor of social order.

Within marriage, Altpeter-Jones says, people’s attention turned to proper gender role behavior. “Gender emerged as one of the most important categories for imagining social order,” she explains.

Sometimes, this focus on gender manifested itself in curious ways. Altpeter-Jones was fascinated by a line of woodcut illustrations—bold black- and-white images that proliferated during the printing revolution of the late 15th century—that showed an imperious wife ruling over her submissive husband. In one, for example, a husband launders clothes while his wife looms over him brandishing a cane.

Marital Quarrel, by Hans Sebald Beham, circa 1535; a mother-in-law beats her daughter’s violent husband.

This “she-man” image, as it was known, serves as a warning: the gender hierarchy depicted here, it proclaims, is entirely upside-down. The she-man appears in marital-advice literature, plays, images, and proverbs, and becomes “the focal point for thinking about gender roles” in this newly ordered society, says Altpeter-Jones.

In her current research into the inter-play between marriage, gender, and order, Altpeter-Jones is most interested in how this post-Reformation gender obsession played out.

In reviewing plays, didactic texts, and illustrated broadsheets of the era, “I was struck by the huge number of texts and images depicting marital violence,” she says. “These depictions are very detailed, graphic, and anatomically specific.”

Altpeter-Jones believes these depictions point insistently to the importance of the body in understanding marriage, gender relationships, and notions of social order. Ultimately, they give us more insight into how people understood the concept of gender.”

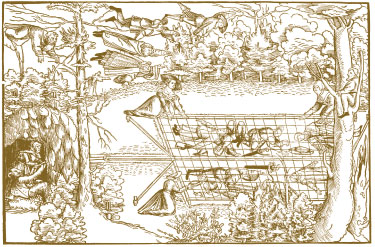

Lover’s Birdhouse, by Niklas Stoer, 1534; monks, peasants, wealthy burghers, and aristocrats are lured into a cage (of fools) by the seductive powers of woman.

Studying gender is a common interest of Altpeter-Jones, who joined the College faculty after earning her doctorate from Duke University in 2003, and Daystar, a German studies major from Lexington, Virginia.

Last semester, Daystar spent six hours a week sifting through literature from the Early Modern period, roughly defined as 1500 to 1750, looking for references to marital violence. “It’s a lot of detective work,” she says. Examining centuries-old writings has given her a new appreciation for literature’s ability to reveal social truths of its era, she says. Studying this particular period also makes her realize how women’s roles in society have fluctuated over time and how the Reformation “revolutionized Western society” beyond the religious sphere.

Alpeter-Jones says that in finding, reviewing, and summarizing works of Early Modern literature, “Tara has been doing a lot of the work I do as a scholar.” As a result, Daystar has become familiar with scholarly research tools and what is required to plan and carry out an academic inquiry— knowledge that will aid her senior-year thesis (in which she plans to compare Turkish immigrant culture in Germany with Hispanic immigrant culture in the United States) and possible graduate school work.

At some point, Daystar hopes to return to Germany—she participated in Lewis & Clark’s Year of Study in Munich as a sophomore—to delve more deeply into German cultural studies. She’s particularly fascinated by how Germans have struggled with issues of national identity, as well as by the country’s prominent role in world history.

Altpeter-Jones plans to submit an analysis of various Early Modern texts on marital violence to the Journal of Women’s History later this year, and will present related findings at a medieval studies conference this fall. Ultimately, she’d like to use what she’s learned so far as a jumping-off point for a broader cultural study of marriage. No matter what historical era is under the microscope, she says, “Marriage is a powerful model for understanding gender and social relationships.”

by Dan Sadowsky

More L&C Magazine Stories

Lewis & Clark Magazine is located in McAfee on the Undergraduate Campus.

MSC: 19

email magazine@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7970

fax 503-768-7969

The L&C Magazine staff welcomes letters and emails from readers about topics covered in the magazine. Correspondence must include your name and location and may be edited.

Lewis & Clark Magazine

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road MSC 19

Portland OR 97219