A Brother Lost—and Found

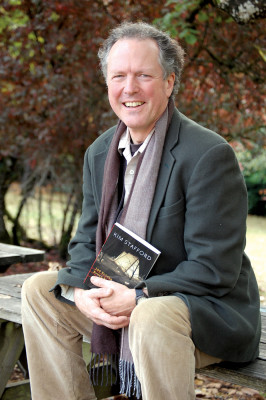

In 1988, Kim Stafford’s brother Bret took his own life. The brothers shared a bright, exploratory childhood together, but grew more distant as adults. When Bret killed himself it was as if a heavy door had swung shut on his story, and the Stafford family expressed its grief and love for one another in a protective silence. Kim Stafford’s new memoir, 100 Tricks Every Boy Can Do: How My Brother Disappeared (Trinity University Press, 2012), opens that door and works backward through the mystery of Bret’s sadness to his happy boyhood. Writing the book, according to Stafford, was a project to “make my brother’s life a whole story again, not just a dark ending.”

Chronicle: Bret died more than 20 years ago—what led you to tell his story now?

Kim Stafford: It took me a long time to realize this didn’t have to be a big book about an impossibly weighty topic—it could be 100 little stories, in bite-sized pieces. This is the same way we teach. We teach many little lessons; there’s not one big lesson and then you’re educated. There’s not one golden 10-minute session with a counselor and you suddenly understand. Understanding is an incremental process.

I say in writing class that a lot of the magic of writing is the trick of just beginning. Just starting to tell the story is an act of forgiveness. A friend of mine said we spend the majority of our energy not saying what we want to say, and not doing what we want to do. We keep the lid on. Once you take the lid off, you’re not at war with yourself anymore. I owe so much to my wife, who said, “Go find solitude, and don’t come back until you’ve started this book.”

There was an episode when I was in Bhutan, at a monastery in a very remote place called the Tiger’s Nest. In this room there were people lighting butter lamps to remember their dear ones. I thought, “I’ll light a lamp for my brother.” The moment I lit it, I started weeping. There was a hissing noise from my tears falling into the flame. I saw a sentence addressed to my brother: “Why did you have to go?” Each word was its own mountain peak, and it would be easier to move the mountains around than to change that chain of words. But then another sentence came: “You had to go.” In that moment, I put down a big stone I’d been carrying.

You clearly inherited the writing and teaching legacy of your father, poet William Stafford. How did his legacy touch you and your brother?

We grew up right outside this window [on the campus of Lewis & Clark]. We lived in a house across the hedgerow there. Our dad had a contract with a “right to fruit” with the college—we would come here and pick the apples, plums, grapes from the old estate. The college was our domain as kids. I inherited that part of our father’s identity and my brother did not. One of the most devastating things I learned while I was writing about the book was the story of a conversation my father had with a friend. “I love all my children but there is one who is myself,” he said.

My brother must have known our father felt that. I suspect that was painful for him.

How is the story of your brother connected to your work at Lewis & Clark?

I started out thinking I was writing this book for my family, but I think it’s for people who have been through darkness. Writing this book my eyes were opened to other people’s suffering. There’s a certain etiquette in many families to not tell what hurts. One kind of love is to protect each other from the difficult dimensions of life. When I started to write the story, the other kind of love became apparent—when you talk about sadness, you are saying, “We’re here in this together.” That is what education and counseling are for.

I have been privy as a teacher to some moments when a class has made a collective decision to tell the truth. They decide for mysterious reasons, “this is a safe place to tell things I’ve carried for too long.”

What feedback have you received on the book so far?

It’s the kind of story you don’t want to inflict on someone else, but when you meet someone who welcomes that dimension of life, we can tell each other amazing things. Even while I was writing the book, many people said to me, “I had a brother, too,” or “That was my dad,” or “My best friend, that’s what happened to him.” It’s like there’s a hidden a language with people who know grief. We have a dialect.

How did you go about writing the book?

I spent days and days writing the table of contents, naming memories and episodes that were not yet written. There are 88 of these fragments in the book. The thing I like about the very short chapter is that it doesn’t have to make a claim or sum anything up. It’s an episode that has remained in memory for reasons of its own. Telling them one by one, they gather toward a greater meaning.

What did you learn about yourself as a writer?

When I started writing, I thought I would remember things and write them down. But it doesn’t work that way. By writing, you learn how to remember. You start writing, and then you recall, “Wait a minute—that other thing happened next.” I love a quote from Norman McLean about this: “Thinking consists of noticing something visible, which leads you to notice something else that’s visible, which leads you to notice something that’s invisible.” Thinking is not a passive activity.

Hanna Neuschwander is director of communications at Lewis & Clark’s Graduate School of Education and Counseling.

More L&C Magazine Stories

Lewis & Clark Magazine is located in McAfee on the Undergraduate Campus.

MSC: 19

email magazine@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7970

fax 503-768-7969

The L&C Magazine staff welcomes letters and emails from readers about topics covered in the magazine. Correspondence must include your name and location and may be edited.

Lewis & Clark Magazine

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road MSC 19

Portland OR 97219