Push and Pull: A Federal Tug of War over Renewable Energy

Open gallery

Fickle federal policies are sending conflicting signals to renewable energy developers. On the one hand, the federal government seems to recognize the critical role that U.S. public lands could and should play in siting the most efficient, productive renewable energy facilities. For example, as I reported a few weeks ago, Congress is considering a bill that would expand leasing opportunities for renewable energy development on federal lands. Similarly, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) has been working with various stakeholder groups to plan for optimal siting of solar power in the desert Southwest. But on the other hand, short-lived federal tax policies designed to spur renewable energy in fact deprive the industry of the certainty needed for steady market growth and drive an unsteady, boom-and-bust cycle of development.

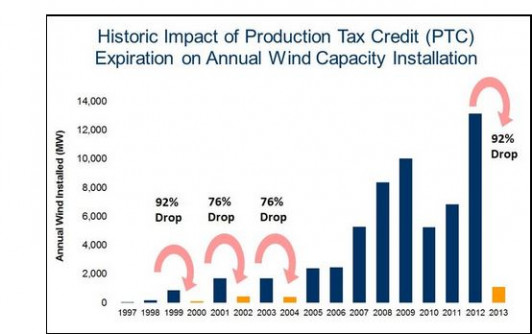

The federal Production Tax Credit (PTC) is the cardinal example of fickle federal policy. Although renewable energy advocates and industry strongly support the PTC, which provides an inflation-adjusted payment for renewable energy delivered to the grid, Congress has allowed the PTC to lapse five times since its initial passage in 1992. The PTC expired most recently at the end of 2013, and although some members of the House and Senate support its resurrection, Congress seems unlikely to act any time soon. The likely consequence is a severe reduction in investment in wind and other renewable energy, as the following graph from the American Wind Energy Association illustrates:

For a detailed discussion of the PTC’s history, functioning, and proposals for its extension or modification, please see Sustainable Energy Subsidies, by the Green Energy Institute’s director, Professor Melissa Powers.

The federal Investment Tax Credit (ITC), which has allowed recovery of 30% of a solar energy system’s cost since 2008, now faces a similarly uncertain future. Unless Congress acts, the ITC will diminish severely at the end of 2016. Large commercial projects will see the credit plunge to only 10% of a project’s cost, while residential projects will no longer enjoy any credit at all. Again, although some members of Congress are attempting to extend the ITC, its fate remains profoundly uncertain. This coming blow risks disrupting the solar industry’s recent trend of record-breaking growth.

In fact, uncertainty over the expiration of the ITC is already impacting solar development. A developer recently withdrew plans for a proposed utility-scale concentrating solar plant in California. Although the developer did not officially attribute the project’s cancellation to the expiring ITC, David Danelski at The Press Enterprise reports that one of the developer’s vice presidents as doubting the project could be completed in time to take advantage of the tax credit before it expires. Mr. Danelski also cites a source from the Solar Electric Power Association, as noting that guaranteed receipt of the ITC is critical for financing solar projects.

The United States should do better. Renewable energy is an important, burgeoning industry that simultaneously offers significant environmental benefits and economic growth. For example, the solar industry now employs more workers than the coal and natural gas industries. Wind energy was the fastest growing source of energy in 2012 and has provided more than a third of new energy-production capacity over the last six years. In 2014 alone, U.S. investment in renewable energy amounted to $7.3 billion.

Stable federal policies are key to fostering this important industry. However, even as federal planning for renewable energy development proceeds, the federal government is failing to offer the kind of certainty that industry requires. The United States has already fallen behind China in solar deployment and lags well behind Europe in the development of offshore wind. Australia provides a chilling cautionary tale: once the 11th largest investor in renewable energy, recent political disputes over the nation’s support for renewable energy have led it to decline to 34th, behind significantly less developed nations like Myanmar. If the United States hopes to be a competitor, much less a leader, in the development of renewable energy, it should pass significant reforms to make federal policies more coherent, stable, and supportive.

More Green Energy Institute Stories

Green Energy is located in Wood Hall on the Law Campus.

email gei@lclark.edu

Director

Carra Sahler

Green Energy

Lewis & Clark Law School

10101 S. Terwilliger Boulevard MSC

Portland OR 97219