Science in the Painted Hills

Open gallery

Faculty members, undergraduates, and high school students work together to unearth the basics of teamwork and field research.

-

Pronghorn antelope, second only to the cheetah in speed, sprint across the Painted Hills of central Oregon. This area, known for its rich geological history, became an extension of the Lewis & Clark campus last summer.

Pronghorn antelope, second only to the cheetah in speed, sprint across the Painted Hills of central Oregon. This area, known for its rich geological history, became an extension of the Lewis & Clark campus last summer. -

The Painted Hills, located in central Oregon, are part of the 14,000-acre John Day Fossil Beds National Monument.

The Painted Hills, located in central Oregon, are part of the 14,000-acre John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. -

Liz Safran, associate professor of geological science and leader of one of the field research teams.

Liz Safran, associate professor of geological science and leader of one of the field research teams. -

High school students Jessica Willis, Catrice Allyene, and Sarah Ramos head toward a classroom at Mitchell High School, where they will prepare presentations about their field projects.

High school students Jessica Willis, Catrice Allyene, and Sarah Ramos head toward a classroom at Mitchell High School, where they will prepare presentations about their field projects. -

Participants camped out on Mitchell High School’s sports field.Bradley Marks

Participants camped out on Mitchell High School’s sports field.Bradley Marks -

One of the field research teams prepares to hike into the body of a giant landslide that blocked the John Day River thousands of years ago.

One of the field research teams prepares to hike into the body of a giant landslide that blocked the John Day River thousands of years ago. -

Associate Professor Elizabeth Safran and members of her field research team look toward a terrace mantled with boulders. The rocks were most likely deposited when an ancient landslide blockage was breached, resulting in a large outburst flood on the John Day River.

Associate Professor Elizabeth Safran and members of her field research team look toward a terrace mantled with boulders. The rocks were most likely deposited when an ancient landslide blockage was breached, resulting in a large outburst flood on the John Day River. -

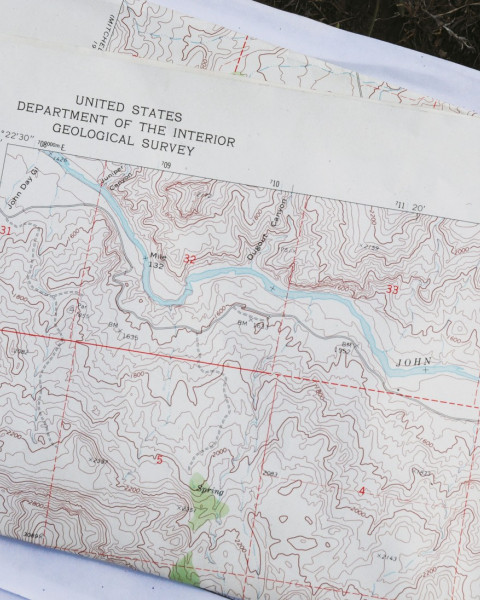

A U.S. Geological Survey topographic map that includes the landslide area

A U.S. Geological Survey topographic map that includes the landslide area -

Associate Professor Liz Safran, Martin Meyer BA ’09, high school student Aaron Romero, and Travis Walton CAS ’10 use an auger to obtain a sediment sample at an ancient landslide site. Finding volcanic ash would help date the age of the slide.

Associate Professor Liz Safran, Martin Meyer BA ’09, high school student Aaron Romero, and Travis Walton CAS ’10 use an auger to obtain a sediment sample at an ancient landslide site. Finding volcanic ash would help date the age of the slide.

by Shelly Meyer

As the afternoon sun dips low in the sky, the alternating soils of the Painted Hills take on their richest hues of yellow, gold, black, and red. Each color corresponds to a different soil type that formed in a long-ago geological era, providing present day researchers with clues to the climate, ecosystems, and geology of the ancient past.

Located 9 miles northwest of Mitchell and 75 miles east of Bend, the Painted Hills are part of the 14,000-acre John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. For a weekend this past June, the area—also known as the Paleo Lands— became an extension of the Lewis & Clark campus for participants in the college’s Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) Collaborative Research Program.

This initiative is part of a four-year, $1.3 million HHMI grant that was awarded to Lewis & Clark in 2008. The grant also provides funds for new interdisciplinary science curricula in the fields of neuroscience, bioinformatics, and biophysics—as well as a course designed for nonmajors that emphasizes the unity of scientific thought. Deborah Lycan, professor of biology, is the HHMI program director at Lewis & Clark. Faculty members from both the College of Arts and Sciences and the Graduate School of Education and Counseling are contributing their expertise to the program.

The HHMI Collaborative Research Program, which is designed to broaden access to science, is structured around the idea of laddered research teams: each three-person team consists of a faculty member, a Lewis & Clark science major, and a high school or community college student. The primary aim is to provide students with a rigorous, lab-based experience emphasizing the collaborative nature of scientific research. In other words, participants explore what a future career as a scientist or mathematician might be like.

Geology in the Field

Before kicking off projects in the lab, program organizers felt it was important for the newly formed research teams to engage in a bonding experience involving real science. Kip Ault, professor of education and director of the outreach component of the HHMI grant, came up with the idea of the Paleo Lands excursion.

Ault teaches science education courses to current and future teachers in Lewis & Clark’s Graduate School of Education and Counseling. In his work, he frequently emphasizes the value of field studies, an appreciation of nature, and the interpretation of local landscapes.

According to Ault, the Paleo Lands trip had two main purposes: to build community among team members and to immerse participants in real scientific inquiry through field research. “Most of the participants had a biology, chemistry, or physics background,” says Ault. “Focusing on geology enabled us to create a novel experience for everybody—culturally, geographically, scientifically. Nobody was on their home turf.”

Participants traveled by van from Portland to their base in Mitchell, a town of just 170 people. There they spent the daytime hours in the Paleo Lands and the nights camping on Mitchell High School’s football field. The biggest hardship? No cell phone service.

The learning experience was titled “Introduction to Geology: Time and Landscape as Research Problems.” Faculty included Ellen Morris Bishop, programs director at the Oregon Paleo Lands Institute and author of the award-winning book In Search of Ancient Oregon; Liz Safran, associate professor of geological science at Lewis & Clark; and Will Boettner, a geologist/paleontologist with Paleo Adventures, Ltd. Each of the three researchers covered a different aspect of the area’s geology.

Students were divided into three groups, each led by one of the faculty members. They were expected to learn about the scientists’ research; help collect data and take good notes; ask questions and work out some hypotheses; and identify future research questions.

For example, Liz Safran’s group studied the area’s ancient landslides, a topic that relates to one of her research projects funded by the National Science Foundation. They examined questions such as: How would you map a feature of this size? How do landslides influence the course of a river? How would you go about dating these land features?

The trip involved real science in real field settings— along with physical exertion in high temperatures. “It was the first time I’d ever gone hiking,” says Aaron Romero, who was a senior at Clackamas High School at the time. “That’s why I enjoyed the trip so much—other than the geological history.”

High school students were nominated for Lewis & Clark’s Collaborative Research Program by their teachers. Most of these students are members of minority populations; many will be first-generation college students. Participating high schools include Beaverton Health and Science School, Centennial Learning Center, Clackamas High School, and Rosemary Anderson High School in Portland.

Lewis & Clark students are selected based on their enthusiasm for science or math, their interest in mentoring younger students, and their academic accomplishments.

Martin Meyer BA ’09, a studio arts and biology major, was one of the Lewis & Clark undergraduates in Safran’s group. “I was intrigued to learn the dynamic life cycle of landslides and the not-so-subtle features that distinguish them from general erosion,” he says. “I was also surprised by the enormous scale of the slides, some of which were many kilometers long.”

The research teams shared their results with the entire group on the final evening of the trip. For many, the presentations were a high point of the experience. “They had only one evening to prepare, but the presentations were terrific,” says Ault. “The Paleo Lands trip was really an appetizer for the bulk of the summer research projects, which were still to come, back in the lab.”

Planning Ahead

Next summer, another trip is planned—most likely to the Paleo Lands. Once again, faculty members, undergraduates, and high school students will team up to study the geological forces that have shaped—and continue to shape—this unique landscape.

Some of the students will be new; others will be returning. But all will contribute their diverse talents, backgrounds, and skills to produce a learning experience rich in layers— like the Painted Hills themselves. ■

To watch a video of the Paleo Lands trip, visit go.lclark.edu/chronicle/paleo_lands.

The HHMI Collaborative Research Program is supported in part by a grant to Lewis & Clark from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute through its Undergraduate Science Education Program.

More L&C Magazine Stories

Lewis & Clark Magazine is located in McAfee on the Undergraduate Campus.

MSC: 19

email magazine@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7970

fax 503-768-7969

The L&C Magazine staff welcomes letters and emails from readers about topics covered in the magazine. Correspondence must include your name and location and may be edited.

Lewis & Clark Magazine

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road MSC 19

Portland OR 97219