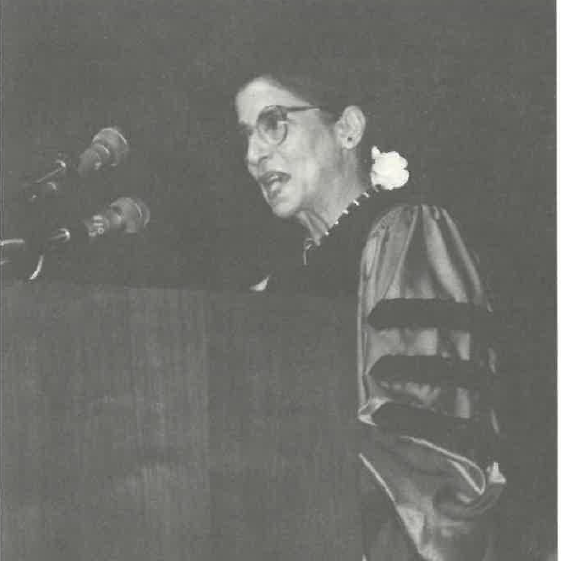

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s 1992 Commencement Speech

Open gallery

The passing of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the second woman to ever sit on the nation’s highest court, saddened the Lewis & Clark community. On September 29, 2020 from 5:00-6:00p.m. the Law School’s Alumni Board is hosting an online vigil to honor and reminisce on this amazing woman’s career and life.

Justice Ginsburg and her husband, Martin Ginsburg, were the law school commencement speakers in 1992, just one year prior to Justice Ginsburg being nominated for the Supreme Court. They were introduced by Dean Steve Kanter who made this prediction, “It is pretty clear that with respect to Ruth Bader Ginsburg that if Gov. Clinton is elected, she would be a logical candidate for the United States Supreme Court.” Following the commencement address, they were both given honorary degrees by the College. Below is the transcript of both Justice Ginsburg’s and Martin Ginsburg’s speeches.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s 1992 Commencement Speech:

“This day marks a grand accomplishment for the class of 1992. We are pleased beyond measure that your Dean has decided to make it a special day for us as well-the first time in our 38-year partnership that we are being honored as spouses-in-law. I will lead off with a few reflections on a great change we have witnessed in the course of our joint venture: the entrance into the legal profession of many sisters alongside brothers-in-law.

Women at Lewis & Clark Northwestern School of Law compose 43% of the student body. That is cause for applause when one recalls not yet ancient days. My law school class in the late 1950s numbered over 500; the class included one black student and less than 10 women. At the welcoming party for the women, the Dean asked each of us to explain what we were doing at the law school occupying a seat that could be filled by a man. (Wishing I could vanish through a trapdoor, and fearful about seeming too assertive, I mumbled that I wanted to understand my husband’s work- he was then in the second-year class.) I am all the more glad to be making these comments at a place associated with a great and brave woman, guide to Lewis & Clark in 1805. Sacagawea, whose courage in the face of danger and deprivation are legendary.

Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor tells a story familiar to students who attended law school in the 1950s, even in the 1960s. Justice O’Connor graduated from Stanford Law School in 1952 at the top of her class, yet no private firm would hire her to do a lawyer’s work. “I interviewed with law firms in Los Angeles and San Francisco,” O’Connor recalled, “But none had ever hired a woman as a lawyer.” (many firms were not prepared to break that bad habit until years after Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 made it illegal.)

When President Carter took office in 1976, no woman had ever served on the United States Supreme Court, and only one woman- Shirley Hufstedler of California- then served at the next federal court level, the United States Court of Appeals. Today Justice O’Connor serves on the Supreme Court, and over twenty women serve at the Federal Court of Appeals level. Two currently serve as Chief Judges of their Circuits.

The few women who braved law school in the 1950s and the 1960s, it was generally supposed, presented no real challenge to (or competition for) the men. The idea was they would devote themselves not too high paying clients represented by law firms, or to top jobs in corporations or in government, but to serving the poor, the oppressed, the truly needy-those who could not pay for legal services. It was true in the 1950s and 1960s, and remains true today, that many women lawyers are sympathetic to, and active in, humanitarian causes, but so are the best men, I believe-the ones who care about the community and world our children and grandchildren inhabit.

An American Bar Association report in the late 1980s expressed concern that lawyers in commercial practice may be losing their sense of perspective and ethics, under pressure from law firms to produce business and billable hours. The report noted the attendant tug on young lawyers to cut back on family involvement, but it ended on an upbeat note. The reporters expressed hope that the increasing participation of women in the profession would have an ameliorating effect. The suggestion was that, by persistently raising the crucial issues of family and workplace, of leave time for parents and daycare facilities, women lawyers could take the lead in bringing sanity and balance to the profession. In this regard, sisters need the aid of brothers-in-law.

To illustrate my point, travel back with me to an incident in the mid-1970s when I was teaching at Columbia Law School and trying to manage a docket of sex equality cases in or headed toward the Supreme Court. The incident concerned my son, then a spirited ten-year-old. You know the kind-challenging as a youngster but now, at age 26, well on his way to becoming human. In my son’s early years, there were calls from the principal almost monthly, requesting a meeting with me to discuss my lively child’s most recent adventure. One afternoon, when I felt particularly weary, I responded: “This child has two parents. Please alternate calls for conferences.” After that, although I observed no quick change in my son’s behavior, the telephone calls came barely once a semester. There was more reluctance to take a father away from his work. I suspect there still is.

But as women join men in many fields of endeavor, as lawyers, engineers, bartenders, computer programmers, we are discovering that personality characteristics for both sexes span a wide range. Immodest aspiration is as evident in some women as it is in some men. Caring for one’s family, on the other hand, sharing and bringing up children or attending to elderly parents, cooking dinners, helping to keep the house in order, no longer mark a man as strange. (To the abiding appreciation of my daughter, son, and now grandchildren, meals at our house for more than a dozen years have been taken completely off Mommy’s track-she has no talent for the job-and switched to Daddy’s-he has mastered the art.)

Yes, large problems still exist. Raising young children, as I just observed, continues to pose more formidable psychological and logistical obstacles for women than for men. But the distance traveled from the 1950s to the 1990s is considerable, and I am optimistic that the trend toward shared roles for men and women, at work and at home, will continue.

There are still those who insist that men inevitably have an edge on leadership opportunity-on power positions at the bar and on the bench- because they are innately more aggressive. In a book published in 1974, The Psychology of Sex Differences, two Stanford University Professors, Eleanor Maccoby and Carol Jacklin, convincingly confirmed a link between aggression and dominance in little boys-and also in apes. But, those authors hasten to add, human boys grow up. The leadership style thought most effective in a civilized society is not the ruthless tough guy who forcibly imposes his will on others. Rather, the qualities that count most are the ability to conciliate among opposing factions and to foster the development of younger, less experienced people in return for their loyalties. These interactive qualities, the kind vital to the successful mediation of controversies, do no appear to be linked to one sex to a greater extent than to the other. Women, I believe, are as generously endowed with them as men are.

Theoretical discussions are ongoing today- particularly in academic circles-about differences in the voices women and men hear, or in the moral perceptions. When asked about such things, I abstain or fudge. Generalizations about the way women or men are-my life’s experience bears out- cannot guide me reliably in making decisions about particular individuals. At least in the law, I have found no natural superiority or deficiency in either sex. I was a law teacher until I became a judge. In class or in grading papers over 17 years, and now in reading briefs and listening to arguments in court for nearly twelve years, I have detected no reliable indicator of distinctly male or surely female thinking-or even penmanship.

In a book published in the 1980s titled Women in Law, a well-known sociologist, Cynthia Epstein, documented how women succeeded in making their way into law schools and thereafter into every kind of legal work, although for too many years they were not wanted. That women lawyers and judges are doing so well, the book comments is not surprising to any but those who harbor prejudice. The study further predicts, and I share this opinion, that not only will women continue to use their law degrees profitably, they will do so with continuing idealism and humanity; simply because those qualities are expected from them. But the author of the study urges, and again I agree, that society should not assign to women, based on traditional notions about the way women are, the primary role of guardian of social consciousness. Humane caring and concern, the author writes, ought not to be regarded as dominantly “women’s work,” it should be regarded as the work of all. That is the grand ideal I have to the 1990s and beyond.

With hearty congratulations to the men and the women of the class of 1992 and to the families who have aided class members on their way, I turn the podium over to distinguished professor of tax law, master chef, and super spouse, Martin D. Ginsburg.”

Martin D. Ginsburg’s 1992 Commencement Speech:

“My spouse, you have heard, began her professional life as a school teacher. I began my professional life as a practitioner in a New York City law firm where I devoted many hours over many years protecting the deservingly wealthy from the predations of the poor and downtrodden.

I was, as you were told but would not have guessed, a tax lawyer. About 15 years ago, wishing others to become as socially useful as I was, I gave up full-time tax practice to teach tax law. More about that shortly.

In my student life and in my professional life, I have had relations with a number of schools. Of none do I think more fondly than I do of Lewis & Clark. My spouse, it is no surprise, holds honorary degrees from many great institutions in the United States and abroad. Until today, I held none and frankly did not believe there existed a college with such a depth of vision that it would honor someone whose calling it is to teach human greed four mornings each week.

One thing I learned in 20 years of practice-and it proved no less useful in teaching-is that a contention will be better received, and better remembered, if it is delivered with some humor. This is not limited to lawyers, Ross Perot, an engineer turned businessman, is a great exemplar. He has attracted enormous public attention, in part because he has more money than Rhode Island, in part because he takes positions on subjects about which it is not always popular to speak, but surely because his way of stating things is catchy and, whether we agree on particulars or we don’t, we get the message.

Midway through the basic tax course, all of you no doubt recall, we ask why tax accounting as often as not fails to follow the rules of financial accounting. The conventional answer is that they are after different things. Financial accounting, seeking to protect creditors is conservative. Tax accounting, seeking to raise revenue, often is anything but conservative. It is indeed the conventional answer, but many students seem to find it inadequate, and I think they are right.

Those of you who did not take the tax course, or enrolled but assiduously failed to attend, may not recall Smith, the President of a growing corporation, who decided that the company should retain a new, larger accounting firm and went off to interview a representative of each of the (then) Big Eight.

“Aren’t all accounting firms the same?” asked his friend Jones.

“We’ll see,” responded Smith.

Two weeks later, the friends met again.

“Were you able to pick an accounting firm?” Jones asked.

“Absolutely,” responded Smith. “I had no trouble at all. I simply asked the representative of each firm how much is 2 and 2. Seven of them said ‘4.’ The eighth asked me if I had a number in mind.”

The pedagogic point of the story, of course, is that tax law and tax administration do not follow the rules of financial accounting because Congress and the IRS do not trust the independence of financial accountants.

When I was a young lawyer, and a younger teacher, I did love that story. It was such fun to malign accountants, owlish fold, whose profession claimed independence but whose subservient practices, we lawyers knew, were very different.

I do not take quite the same joy these days in my “How To Pick An Accountant” story.

It has something to do with how lawyers these days are viewed by others, and how lawyers see themselves. I propose to speak, briefly I promise, about professional responsibility.

My father, a good and sensible businessman, hated lawyers. He called them “No People.” Whenever my father came up with what he conceived a clever idea or a novel transaction that made good business sense, the lawyers told him “no.” Either it was illegal or the cost of meeting the law’s requirements was prohibitive.

Were these No People always wrong? Surely not. My father had as many flaky ideas as the next client.

Were these No People always right? I seriously doubt it.

Our legal system, as each of you has certainly discovered, is lunatically complex. “Getting to yes” too often demands of the attorney an extraordinary degree of professional skill. The strain placed on the less experienced or less specialized practitioner can be painful. The overwhelmed lawyers may just say “no.” On the other hand, the overwhelmed lawyer who wants the answer to be “yes” but lacks the professional skill to get there, may feel pushed to cut the corner, to get the yes by cheating “just a little.”

After all, if I may repair to a litany of my own discipline, the tax return may not be audited, if it is audited the auditing agent may miss the issue, if the agent sees the issue perhaps we can talk the agent out of it, if we cannot talk the agent out of it mauve we can settle it favorably, and so on down the slope.

I do appreciate that professional irresponsibility may proceed from a cause other than a lack of professional skill. There are lawyers, some extremely able, who so identify with the client’s expansive wishes as to become moral, and on occasion legal, co-conspirators. The Savings and Loan mess furnished some high profile examples.

I offer a short story that sounds apocryphal but is, I swear, true. As a young lawyer, a third-year associate, I was working with some clients in the securities brokerage business. They were “close to the line” people, even I could see that, but they were worldly and clever and I really liked the work. The firm’s then-senior litigation partner, an experienced crusty gentleman, called me in one day for a short talk. He wanted me to know the maxim by which he had lived his professional life. It was-I quote him precisely–“if someone goes to jail, be sure it’s the client.”

I understood that advice as a reminder that we may be the client’s advisor and, to the limits of propriety, the client’s advocate, but we are not the client’s partner.

History may not characterize as cause for celebration the performance of lawyers during the Savings and Loan salad days, but pendulums do swing. In 1965 it was the published position of the American Bar Association- in a, so help me, ethics opinion- that a tax lawyer, in discharging a duty of “warm zeal” to the client, was entirely free to render a warmly favorable opinion, even though the lawyer believed no court was likely to so hold, just so long as there was a “reasonable basis” for the favorable opinion. A reasonable basis, the ABA made clear, was to be sharply distinguished from an “honest belief,” and many practitioners quickly concluded that “reasonable basis” translated as “anything north of frivolous.” I am happy to report that, pressured as much by honest practitioners as by the IRS, the ABA not too long ago reversed course and embraced a more palatable standard of “realistic possibility of success.” Not a giant step for the honor of the profession, perhaps, but an improvement surely.

I do not suppose, however, that either professional competence or professional responsibility of an appropriately high order can be “legislated.” Impediments, such as that embarrassing 1965 ABA ethics opinion, can be removed and better training can be offered in and after law school, but in the end, each of us does for himself or herself.

And each of us does well to recall that 2 and 2 really is 4, and while on special occasions 2 and 2 may be 22, on no occasion is 2 and 2 whatever advantageous number the firm’s most valued client happens to have in mind.

I join my super spouse in extending warmest congratulations to the men and women of the Class of 1992 and to their families.”

Law Communications is located in room 304 of Legal Research Center (LRC) on the law Campus.

MSC: 51

email jasbury@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-6605

Cell: 626-676-7923

Assistant Dean,

Communications and External Relations, Law School

Judy Asbury

Law Communications

Lewis & Clark Law School

10101 S. Terwilliger Boulevard MSC 51

Portland OR 97219