Liberty and Justice, After All

Open gallery

by Ellisa Valo

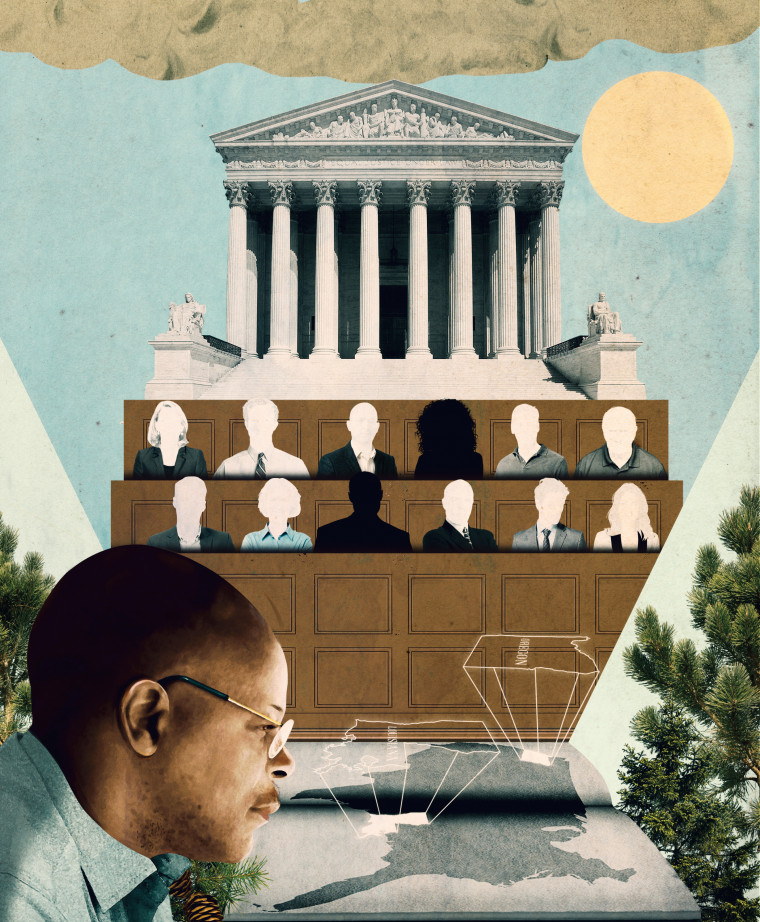

Illustration by Laurindo Feliciano

Lewis & Clark Law Professor Aliza Kaplan chooses her words thoughtfully as she describes her good friend and first-year law student Calvin Duncan: “Calvin is smart. He’s filled with empathy. He takes nothing for granted. He’s a peacemaker. And he doesn’t give up,” she says. “The reason why we don’t have nonunanimous jury convictions anymore is because Calvin didn’t give up.”

At 57, Duncan may be one of the most experienced—and tenacious—law students ever to attend Lewis & Clark. With 28 years of prison time behind him for a crime he didn’t commit, 23 years as a jailhouse lawyer, and a U.S. Supreme Court win to his credit, his journey to law school has been nothing short of extraordinary.

Kids from his neighborhood, a community built on top of an old city dump in the Ninth Ward of New Orleans, didn’t grow up thinking they’d go to law school. “We grew up thinking we’d go to prison or get killed,” says Duncan. “That was it.”

Hoping to avoid that future, Duncan left school after the ninth grade and joined the federal Job Corps to get out of New Orleans—but not before making a mistake that later cost him dearly. At 14, he was arrested for shoplifting clothes to wear to school. Four years later, in 1981, the mug shot on file from that early incident was used to misidentify him as a suspect in a Louisiana homicide.

Though he had spent time in Louisiana between Job Corps projects, the first he heard of the crime was when he was on assignment with the Job Corps in Oregon—his aunt mentioned she had seen it on the news. The next time was when two Oregon detectives came to his job site to arrest him on a Louisiana warrant. He was working at the Timber Lake Job Corps Civilian Conservation Center at the time, studying for his GED, learning welding, and finding a deep sense of peace in the Mount Hood National Forest. “I was just getting my life together,” he says, “and I didn’t see daylight again for 28 and a half years.”

Learning Law From the Inside

Duncan was extradited to Louisiana to await trial, facing a possible death penalty. “I asked everybody on my unit: how can I save myself?” he recalls. “They all told me: you need to learn the law.” So, at 19, with only a ninth-grade education, Duncan started studying. He read everything he could get his hands on, but materials were scarce in jail. His first law book was one that he created himself from newspaper clippings about prominent cases. When he needed the real thing, he filed his first motion, “A Motion for a Law Book,” and sent it straight to the Louisiana Supreme Court. The high court politely referred it to a lower court. He got the book. “Now I considered myself a lawyer,” he remembers.

His wait for a jury trial went on for two and a half years. The trial lasted one day. Duncan was convicted and sentenced to spend the rest of his life in the Louisiana State Penitentiary, known as Angola.

At Angola, Duncan applied for a job as an inmate counsel substitute, also known as a jailhouse lawyer. He got the job, and in the ensuing years, he got his GED and took a paralegal class offered to inmates. “I was putting the pieces together,” he says. While continuing to try to prove his own innocence, he turned his attention to helping fellow inmates with their legal issues, and he became good at it, securing the release of several wrongfully accused people. As his knowledge grew, he started teaching law to other inmate lawyers, and lawyers on the outside began to seek his advice on criminal cases.

In reviewing inmates’ cases, Duncan started to notice that some had been convicted even though their juries had not reached unanimous decisions. He did some research and discovered that felony convictions by nonunanimous juries were allowed by state law in just two states: Louisiana and Oregon, the two places he had called home. The Supreme Court upheld these laws in 1972, “So that was the law,” says Duncan. “But I didn’t agree with it.” He began to challenge nonunanimous verdicts when he came across them, but time after time, the courts told him, “The law is clear. Denied.”

Continuing the Work on the Outside

After nearly 30 years in prison, Duncan was finally freed on January 7, 2011, with the help of Innocence Project New Orleans, an organization that works to free innocent people who are serving life sentences. “I got out on a Friday,” he says, “and the next Tuesday, I’m on the Tulane campus trying to figure out what I need to do to get to law school.” Soon the former jailhouse lawyer was working on his undergraduate requirements, earning a paralegal degree from Tulane University in 2018.

Meanwhile, his work for people on the inside continued on the outside. Within days of his release from prison, Duncan was employed full time at the Capital Appeals Project, a nonprofit law firm representing people on death row in their appeals. “All their clients were my clients when I was in prison,” he says.

Two years after his release, he was awarded a Soros Justice Fellowship and used the funds to create The Light of Justice, a project that helps inmates and inmate lawyers obtain the legal materials and records they need to gain access to the courts.

During all this time, the nonunanimous jury issue continued to eat at him. His own jury had been unanimous and had gotten it wrong. How many more people were in prison because of nonunanimous verdicts—decisions that would have resulted in mistrials in any other state? At the Louisiana Supreme Court Law Library, Duncan dug further and discovered that the Louisiana law had been the product of an 1898 constitutional convention whose purpose, according to a committee chair, was “to establish the supremacy of the white race” in the state. Already under the threat of a federal investigation for excluding African Americans from juries, Louisiana found a new, less visible way to discriminate. By allowing 10-2 jury verdicts, it ensured that even if one or two Black people did make it onto the jury for an accused African American, their votes wouldn’t count. “Before, I just thought it was the law,” says Duncan. “But now I realized it was based on racism.”

Duncan approached lawyer and coworker Ben Cohen with this new information, and said, “Let’s start litigating these cases again.” Cohen enthusiastically signed on. Starting with inmate lawyers, they began selecting cases, working toward getting one in front of the U.S. Supreme Court. In the process, Duncan’s path intersected with that of Lewis & Clark Law Professor Aliza Kaplan.

Kaplan was waging a similar legal campaign from Oregon. “I became freaked out by the very existence of the Oregon law when I moved here 10 years ago,” she says. “How could this even be? What is reasonable doubt if two dissenting jurors don’t count?” When Kaplan took a closer look at the issue a few years later, she discovered that Oregon’s law, like Louisiana’s, had discriminatory origins. In Oregon, the law traced back to anti-Semitic, anti-Catholic, and anti-immigrant efforts by the rising Ku Klux Klan. “When I learned the history, that’s when I started developing relationships and collaborating with the folks in Louisiana,” she says. “And one of them was Calvin.”

Over the next few years, Duncan and Cohen wrote multiple briefs on behalf of Louisiana inmates, while Kaplan, assisted by students in Lewis & Clark’s Criminal Justice Reform Clinic, provided the Oregon perspective. “The issue was so personal and passionate for all of us,” she says, that the colleagues quickly became good friends.

In 2018, voters struck down the Louisiana law, “but that only applied to people going forward,” says Duncan. “What about all the people who were already in prison?” He continued to press the U.S. Supreme Court, “and after 23 tries,” he says, “after so many years, the court finally said, we’re going to hear one of these cases.”

In October 2019, the Supreme Court of the United States heard oral arguments in one of Duncan’s cases, Ramos v. Louisiana. He and Kaplan sat side by side in the front row during the proceedings, hardly believing it was happening. On April 20, 2020, the court announced its decision: “They said we was right,” says Duncan, “that the law was unconstitutional.” The opinion, he notes with satisfaction, explicitly calls out the law’s racist roots.

Starting Over Where Everything Ended

Five months after his Supreme Court victory—and nearly 40 years after his wrongful arrest in Oregon—Calvin’s life came full circle as he returned to Oregon, this time as a law student at Lewis & Clark. Despite his complicated history with the state, he finds poetic justice in his return. “In prison, you’ve got to have a healthy way of thinking to survive,” he explains. “My thinking was, the one place that would help me begin my life all over again is the place where it ended—a place where I’d initially found so much peace.”

At Lewis & Clark, he is enjoying every moment of the present and looking forward to a bright future. He thinks about studying environmental law, “to help children grow up in a better environment than I did,” he says. And no matter what, “I’m always, always going to help people in prison,” says Duncan. “Until we come together as a society to address some of these problems, I want to help protect people.”

But of course, he is already doing that. He’s never stopped. Kaplan connected with him recently about one of the law clinic’s clients—a man who’d maintained his innocence on death row for 34 years and had finally been paroled with the clinic’s help. “This man is overwhelmed and has very little support,” Kaplan told Duncan. He responded immediately. “Calvin is going to be part of this man’s community now, making sure he’s OK,” she says. “That’s who Calvin is.”

—Ellisa Valo is a freelance writer in Oregon City.

The Ramos Project

Fighting for retroactive justice in Oregon

When the Supreme Court ruled nonunanimous felony convictions unconstitutional in Ramos v. Louisiana, it left open the question of retroactivity. Professor Aliza Kaplan, who directs the law school’s Criminal Justice Reform Clinic, launched the Ramos Project immediately following the April 20, 2020, ruling to press for an answer.

“My argument is, of course the law should apply retroactively,” she says. “It shouldn’t matter when your case happened, right? You either have the constitutional right to a unanimous jury verdict or you don’t.”

Through the project, she and a team of current and former students have helped close to 550 people file challenges pro se (on their own behalf) and have built a rich repository of materials to assist lawyers working on cases throughout Oregon.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments on retroactivity in December. A decision is pending. Until then, or until Kaplan’s team persuades the Oregon Supreme Court to rule on a case, she and her students keep litigating the issue, one case at a time.

More L&C Magazine Stories

Lewis & Clark Magazine is located in McAfee on the Undergraduate Campus.

MSC: 19

email magazine@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7970

fax 503-768-7969

The L&C Magazine staff welcomes letters and emails from readers about topics covered in the magazine. Correspondence must include your name and location and may be edited.

Lewis & Clark Magazine

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road MSC 19

Portland OR 97219