Forget the Alamo

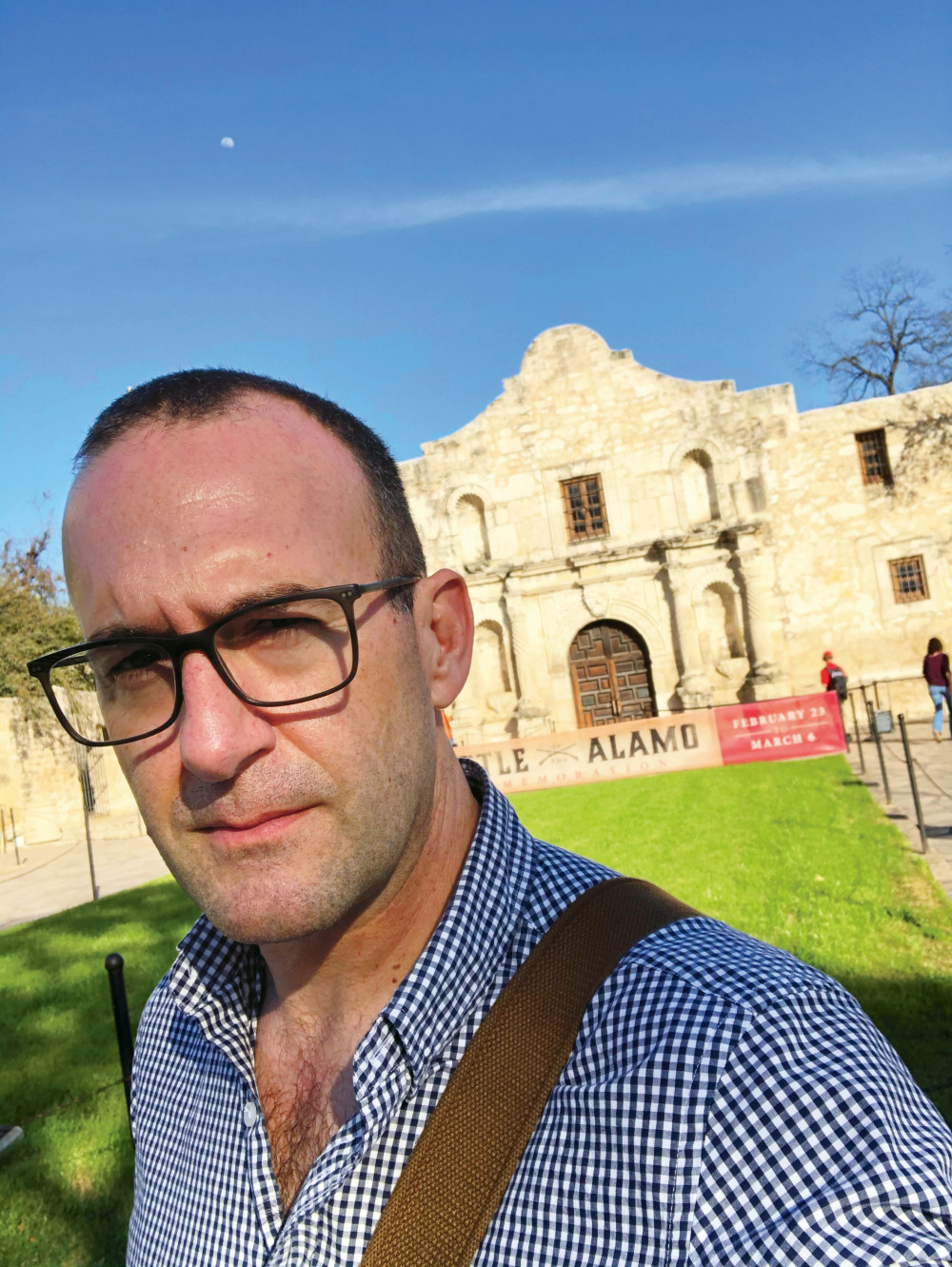

As a Russian studies major at Lewis & Clark, Jason Stanford BA ’92 spent his last semester in Moscow and ended up staying another two years. During that time, he led a strike of foreign workers against a Russian boss. He also learned that U.S. economic aid was being funneled to Boris Yeltsin’s political party, a scoop he uncovered for the Los Angeles Times.

WHO

Jason Stanford BA ’92

YOUTHFUL AMBITION

To be a Cold War spy.

POLITICAL EXPERIENCE

Strategist and opposition researcher; mayoral communications director.

CURRENT POSITION

Chief of communications and community engagement for the Austin Independent School District.

SURPRISINGLY USEFUL L&C ACTIVITY

Rowing crew. “Every cell in your body wants you to quit, and being able to keep going despite the pain and the struggle is horribly analogous to writing a book.”

In other words, Stanford doesn’t shrink from controversy. It’s a trait that has served him well in Texas, where he moved in the early 1990s to work on political campaigns for Governor Ann Richards and other Democrats.

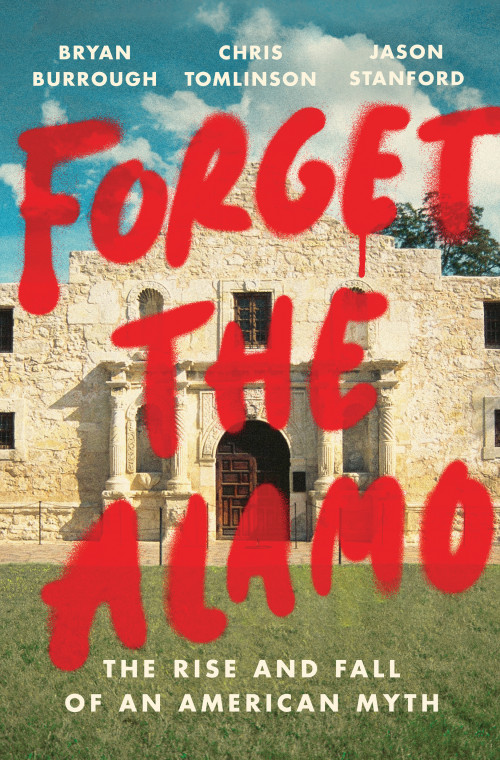

That willingness to take sides came in especially handy this year, which saw the publication of Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of an American Myth, a book Stanford cowrote that pokes holes in Texas’ most cherished origin story. Forget the Alamo challenges the claim that Davy Crockett and a small band of brave Texans all fought to the death at a San Antonio mission to defend their freedom against the tyranny of Mexico. Instead, it advances the thesis that Crockett, William Travis, and other Alamo defenders fought, in large measure, to maintain their slaveholder status. Mexico had outlawed slavery in 1829, creating tensions with white slaveholders in what would later become the state of Texas.

Many contemporary historians have already challenged what Forget the Alamo calls “the Heroic Anglo Narrative,” which minimizes the role of Tejanos in the Texas rebellion. But the book’s most audacious chapter pivots to another issue: a $15 million collection of historical artifacts said to have belonged to Crockett, Jim Bowie, William Travis, and other Alamo martyrs.

In 2014, the collection’s owner, Phil Collins—yes, that Phil Collins, the British pop star—donated this treasure trove to the Alamo on the condition that it be prominently displayed there. A $450 million plan to completely refurbish the Alamo’s badly outdated visitor center was drawn up. Embarrassingly for everyone involved, Forget the Alamo makes a hard-to-refute case that the collection is riddled with fakes, some of which were “authenticated” solely by psychics.

Sidestepping the problem of the bogus artifacts, Alamo traditionalists have come out noisily against the book’s reassessment of Alamo history. Bowing to objections from state GOP leaders, the Texas State History Museum abruptly canceled a highly publicized reception and book talk. Texas Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick calls the book “a fact-free rewriting of Texas history” and posted a point-by-point critique on his blog.

Stanford isn’t fazed. “They like to say that politics is ROUGH in Texas, a full-contact sport,” says Stanford. “But there are no tanks being called out to shoot at protesters. And political rivals don’t murder each other like they do in Moscow,” he notes. “Being a Russian studies major, especially in the early ’90s, has helped me put what’s happening in Texas in its proper perspective.”

Stanford says the book’s publisher, Penguin Press, expected Forget the Alamo to be a regional book, but it has become “more of a national thing,” with reviews in the Washington Post, the New York Times, and the Wall Street Journal. The Phil Collins connection doesn’t hurt. Neither does the high visibility—and changing ethnic makeup—of Texas politics. For instance, the commissioner of the Texas General Land Office, who oversees the Alamo complex, is George P. Bush, the mixed-heritage son of Jeb and Columba Bush, who was born and grew up in Mexico.

For Stanford, the biggest surprise about Alamo history isn’t that the battle wasn’t fought exactly the way it’s been portrayed in movies and songs. “The biggest surprise,” he says, “was how the Alamo has ‘othered’ the Hispanic population of Texas. In seventh grade history, Mexican-American students are taught that they are the bad guys. The way that the Alamo has been taught in school and in popular culture has made the original residents of this state feel like they’re in a foreign country … like it wasn’t theirs. The Alamo became a white people’s history, and it’s alienated what is becoming the majority population of the state.”

Researching and writing the book, he notes, was surprisingly reminiscent of the experience he shared with all Lewis & Clark first-years in the late 1980s. In the required course known as Basic Inquiry, students were encouraged to question their most basic assumptions about the world. “Doing a book like this,” he says, “rewards you for not knowing the answer. It rewards you for being able to ask lots of questions and to keep after it until you find the story.”

—by Angie Jabine

More L&C Magazine Stories

Lewis & Clark Magazine is located in McAfee on the Undergraduate Campus.

MSC: 19

email magazine@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7970

fax 503-768-7969

The L&C Magazine staff welcomes letters and emails from readers about topics covered in the magazine. Correspondence must include your name and location and may be edited.

Lewis & Clark Magazine

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road MSC 19

Portland OR 97219