A Cancer Researcher of a Different Stripe

Open gallery

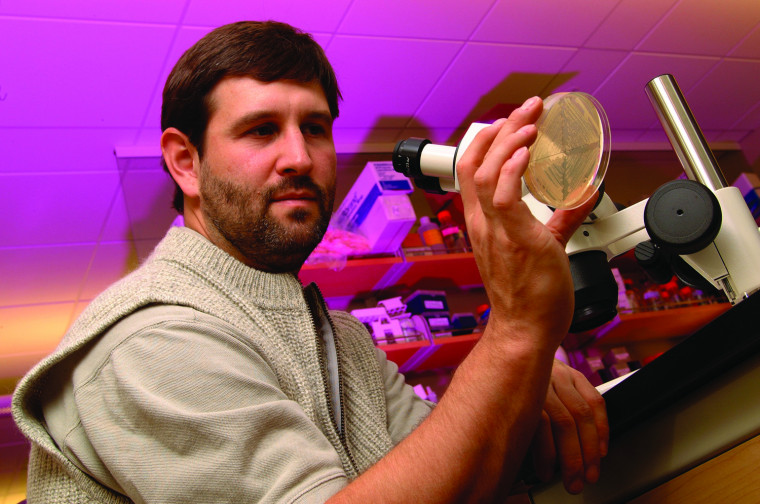

For someone who holds a prestigious appointment at a premier cancer research center, Brad Cairns spends a lot of time staring at zebra fish.

These aren’t just any zebra fish, however, and Cairns doesn’t regard them with the mesmerized gaze of an aquarium aficionado. When he studies them, he is researching how gene activation and suppression differ in cancer cells versus normal cells, how that difference leads to tumor growth, and how to design targeted therapies that may restore healthy cell development.

It’s research that puts him at the forefront of critical inquiry, and it demands collaboration, rigorous technique, and innovative thinking–qualities he first honed as a chemistry major at Lewis & Clark.

Two professors in particular provided “exceptionally important and formative scientific experiences” that helped shape his career. Chemistry professor Jim Duncan immersed Cairns in the rigorous technical demands of formal research, and Pamplin Professor of Science Janis Lochner introduced him to molecular biology and the world of interdisciplinary thinking. “The professors at Lewis & Clark provide inspiring teaching and training,” he says. “They are fully engaged in the forefront of scientific and medical research and knowledge.”

Building on his Lewis & Clark experiences, Cairns earned his PhD at Stanford, with Nobel laureate Roger Kornberg as his advisor, and did postdoctoral research at Harvard. He is now a professor in the department of oncological sciences at the University of Utah’s Huntsman Cancer Institute.

His research has been covered in several scientific journals and earned him a prized appointment as a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator in 2000. HHMI support has given him the freedom to take innovative approaches in unraveling the complex mechanisms and processes that contribute to leukemia, colon cancer, and developmental defects, especially in children.

So why study zebra fish?

Cairns and his colleagues had determined the ways genes switch on and off in normal development in the one-celled organism popularly known as baker’s yeast. Eager to extend their work to more complex organisms, they partnered with other researchers at Huntsman using zebra fish to study genes associated with blood-borne cancers.

“Collaboration is essential because many of our biggest discoveries and breakthrough moments come at the boundaries–the areas where different disciplines intersect,” says Cairns of his work with his colleagues. “We had isolated key factors that control gene expression in yeast cells–factors that have nearly identical counterparts in zebra fish and human cells. We have the tools to knock out and manipulate these factors in zebra fish and examine their impact on cell growth and cancer, and these tools are not readily available in human cells.”

The research is one more step in a long road toward building “a toolbox of concepts that can be applied to cancer formation in human cells,” says Cairns. “As cancer researchers, we’re all part of that process.”

–by Deanna Oothoudt

More L&C Magazine Stories

Lewis & Clark Magazine is located in McAfee on the Undergraduate Campus.

MSC: 19

email magazine@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7970

fax 503-768-7969

The L&C Magazine staff welcomes letters and emails from readers about topics covered in the magazine. Correspondence must include your name and location and may be edited.

Lewis & Clark Magazine

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road MSC 19

Portland OR 97219