Anthropologist wins NEH grant to create digital archive of Judaic Moroccan papers

Open gallery

What began with simple curiosity about a small room filled with bags of papers in a synagogue in Rabat, Morocco, has become a project that will help change the way anthropologists and historians document cultures around the world.

Oren Kosansky, assistant professor of anthropology, has earned a $50,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to develop a digital archive of Judaic Moroccan documents from the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries. The online archive will open access to researchers with an interest in Jewish culture in Northern Africa and allow them to share ideas and information widely. Of even greater interest to the NEH, the project will offer a new model for intercultural and international collaboration in the creation of technological resources to share historical information.

Making a discovery

Kosansky’s fascination with Judiaism in Morocco dates back to his graduate work in the early 1990s. In 2005, a Fulbright research grant took him to Rabat, the capital of Morocco and former home to a large Jewish community. During his stay, Kosansky worked closely with leaders of Rabat’s major synagogue and community center. It was there that he discovered a genizah—a room or depository found in synagogues, where old religious documents that are no longer in use are kept and periodically buried.

“In Judaic tradition, documents containing references to God are forbidden from being destroyed,” Kosansky explained. “Most obviously books and papers on religious topics such as the Torah are deemed sacred and treated in a ceremonious fashion, but any item with religious or legal references—such as a wedding announcement or business contract—would also be kept.

“In this case, I found literally thousands of books and documents pertaining to virtually all facets of Jewish life in Morocco, especially as it was transformed during the 20th century. My first thought was, ‘How can I save these materials from burial, so that they can be consulted by community members and scholars.’”

Kosansky noted that the Jewish community in Rabat once numbered in the thousands and had dwindled to fewer than 100, following a broader trend of emigration that brought the majority of Moroccan Jews to Israel, France, and other global destinations. As an anthropologist, he saw great potential for research materials that could serve many in his field.

“Written materials are very important in Judaism,” Kosansky explained. “It is a very textual culture. These documents offer great insight into a culture and a community of people that once thrived here. They offer an opportunity to investigate elements of a society that has not been fully explored by those of us in the academic field. For the Jewish community, it represents something perhaps even more valuable—an opportunity to reflect on how their traditions have been shaped by modern life, colonialism, technological change, and global networks of migration, communication, and commerce.”

With the approval of community leaders, Kosansky sorted through hundreds of sacks containing thousands of documents and determined which documents were appropriate for burial and which represented significant historical texts suitable for preservation. Synagogue leaders gave Kosansky the documents for preservation, and he donated them to the Jewish Museum in Casablanca.

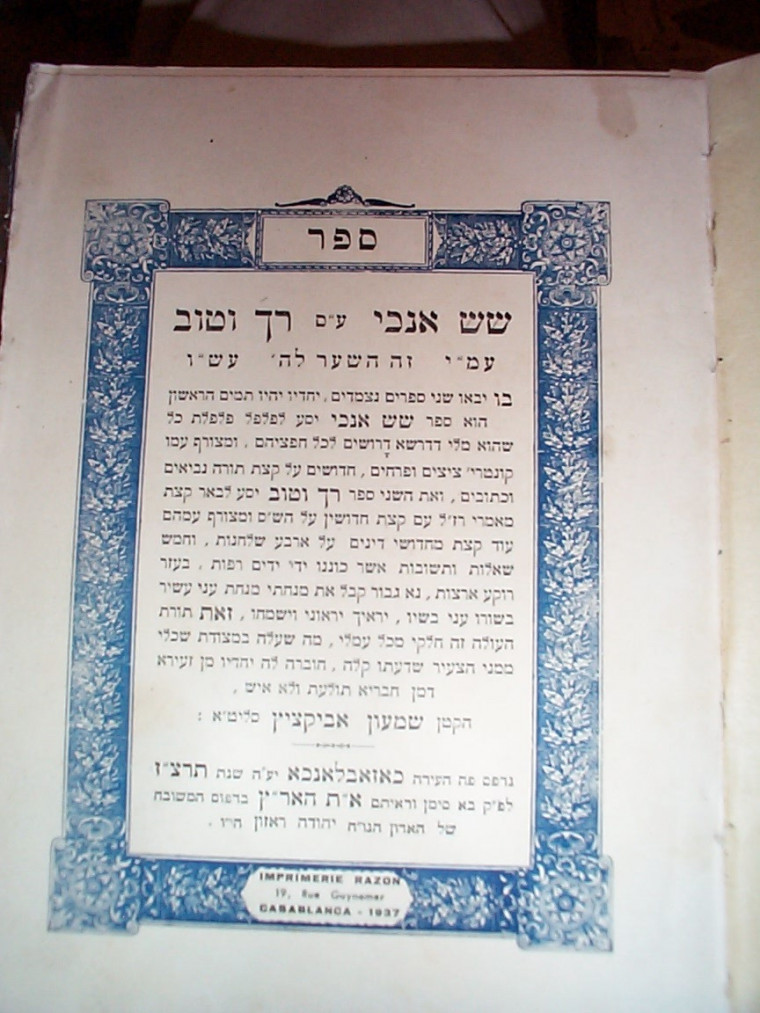

The unparalleled collection contains many unique documents, including handwritten letters, unpublished manuscripts, and community records, as well as published materials in a variety of languages, including Judeo-Arabic, Hebrew, and French. The documents now held by the museum will be the focus of Kosansky’s NEH digitization project.

Building a model to bring disparate parties and countries together

In developing his project, Kosansky has faced many difficult questions and considerations. Despite his excitement about the opportunity to open the door further on North African culture, he wrestled with concerns about how to build such an archive—chief among them, how to build an equitable process that respects the legal, ethical, and social differences across several societies.

“There are so many issues up for consideration,” Kosansky said. “For example, what, if any, are the copyright issues for such old documents? And what are the copyright laws in Morocco? Are there private documents we shouldn’t digitize out of respect for some individuals or the Jewish community? Who should be consulted on such ethical considerations?”

Kosansky will begin the project while he is directing Lewis & Clark’s first overseas program in Morocco next spring. Over the next 18 months, he will be identifying experts both in the U.S. and in Morocco in diverse fields like digital archives, information access, intellectual property law, and Jewish history to address the legal issues, begin the digitization process, and have the website built.

Given the scope of the entire project, Kosansky feels the key to its success will be building a shared vision and understanding across languages and cultural differences.

While the circumstances for any future project will be unique to the people and part of the world it is happening in, NEH will be better prepared to fund and assist comparable projects based on Kosansky’s experience and the lessons he takes away.

“This is about far more than an archive,” Kosansky said. “And it will be more than a list or set of images. It will be organic in its process and in its outcomes. I’m looking forward to the opportunity to learn how to effectively bring a cross-cultural project to fruition and to develop a model for academicians and laypeople to share information and ideas about the documents that they access.”

More Newsroom Stories

Public Relations is located in McAfee on the Undergraduate Campus.

MSC: 19

email public@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7970

Public Relations

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road MSC 19

Portland OR 97219