Seeing the Forest and the Trees

How to do groundbreaking research in eight (not so) easy steps, with Assistant Professor of Biology Margaret Metz

by Kim Catley

Conducting field research in the Amazon rainforest sounds enticing on its surface. Perhaps you imagine spending your days immersed in the constant hum of insects as you trek through lush vegetation. Or maybe you visualize standing at the foot of a towering waterfall as exotic birds soar overhead.

The reality, however, looks a little different.

Every summer, Assistant Professor of Biology Margaret Metz travels to eastern Ecuador, where she gathers data about trees in the Amazon. The days are steamy and often tedious as Metz and her team of undergraduates carefully search for seedlings, which they’ll track from year to year.

The seeds that fall this year will be measured as seedlings the next, becoming part of a data set that will be tracked for years to come. Her students will come and go, each spinning off on their own paths within or beyond the field. But with each data point Metz collects and analyzes, she’s creating a more complete picture that will help us understand how tree species survive and thrive and how climate change might be creating extreme conditions that could lead to the collapse of rainforests.

Here, Metz describes what it takes to live and learn in the field.

1. Start with a hypothesis.

There are plenty of reasons why tropical environments like the Amazon have such high biodiversity; Metz wants to know how that diversity is maintained over time.

Some theories consider how a tree’s enemies—fungi and insects —might keep a species from becoming too common, thereby allowing more species to coexist. There’s also the possibility that this diversity is random. Some years, a plant produces more seeds; other years, that productivity declines without any rhyme or reason.

“If these different hypotheses hold, then we should expect to see a response in what the plants are doing,” she says. “If, for example, environmental conditions are important, then we should see certain species doing well in some conditions and not in others. We can take these hypotheses and make predictions about where plants live or die.”

Through a recent grant, Metz is trying to separate signals of climate change from natural cycles like El Niño. “We need years of data to detect the difference between man-made and natural influences,” she says. “We can’t just watch the number of seeds or seedlings go up for three or four years and say, ‘This is from climate change.’”

2. Collect the data in the field.

Since 2002, Metz has been tracking the germination and growth of seedlings in 600 plots within a research station at Yasuní

National Park in Ecuador. Every year, she takes a group of undergraduates to measure existing seedlings and tag new growth—a challenge in a forest with at least 1,200 distinct species of trees.

“In that high-diversity system,” she says, “it’s really hard to do experiments or to understand some of the mechanisms more deeply, just because we don’t know what most of the species are.”

That’s why Metz has extended her research to the central coast of California and the Columbia River Gorge in Washington, where the forests might have just 10 species of trees—mostly redwoods, bay laurel, and tanoak. In California, she’s studying a landscape that is both prone to fire and has a pathogen, known as sudden oak death, which is killing millions of trees. Metz is trying to determine how the disease was introduced, its role in shaping the diversity of the forest, and whether it’s making fires worse by increasing the amount of available tinder.

Metz sees connections between the forests—and so do the students who travel with her. Lauren Walker, a senior biology major, was surprised by the way that the unique environments of Ecuador and Washington infused certain parts of the research process.

“Our research methodology is essentially the same, but the conditions are completely different,” Walker says. “With the Washington project, we’re working with a limited number of common species. This allows me to sort seeds and identify them with a degree of confidence. When we’re working in Ecuador, we need a local expert to identify the seeds and seedlings.”

3. Prepare for the grind.

“It looks glamorous,” Metz says. “I go off to the rainforest with my students, and we have this big adventure.

Credit: Robert M Reynolds“But the actual work is many hours a day kneeling down, slapping away bugs. It’s muggy and hot. We’re at a research station with very little communication with the outside world. We have to be as careful with the measurements for the first plant as we are with the last, even though we’ve done the same thing a thousand times.”

Processing the data requires just as much precision and attention to detail. Back in her lab at Lewis & Clark, Metz and her students spend months hunting for seeds, calculating survival and growth rates, studying photos, and looking for patterns in the environment.

“It’s like Where’s Waldo? except we’re searching for tiny seeds,” says Mila Pruiett, a sophomore biology major who worked on Metz’s Washington project. “Counting these tiny things is really important because it allows us to calculate germination rates over time. It’s a way of connecting our daily work with the study’s five-year plan.”

Walker says the experience is a lesson in how research actually gets done. “It is so cool to see the scientific method in action,” she says. “It humanizes the complex scientific papers I read for my classes.”

4. Master the behind-the-scenes details

“The logistics of coordinating field research are very cumbersome,” says Greta Binford, professor of biology and department chair. “It’s hard to pursue scientific questions with rigor under the best of circumstances, but to do it in these complex forests with undergraduates requires a whole new level of expertise. Margaret is masterful at it.”

Binford adds that Metz has been particularly successful at securing funding for her research (all three projects are supported by the National Science Foundation). This requires Metz to maintain a steady workflow of research, from data collection and analysis to writing, publishing, and dissemination.

Metz does all of this while working with collaborative teams who share complex data sets, spread across three localities, and balancing a full teaching load.

“One of the amazing things about Lewis & Clark is that no one has told me that I shouldn’t pursue the research or grants I want,” Metz says. “Our research makes us better teachers, and teaching makes us better researchers. But it’s hard to juggle, because teaching and mentoring can take up all of your time. I also need time to write grants and perform the analysis my students don’t yet know how to do.”

5. Find and nurture your unstoppable team.

Working with a team of undergraduates is a delicate balance of training future researchers while trying to make steady progress on the task at hand.

That’s why the students who join Metz in Ecuador have to meet certain criteria. They’re typically interested in ecology or environmental issues and like being outside. Metz requires them to be proficient in Spanish and have strong quantitative minds.

“It’s not just about having this rugged adventure,” Metz says. “I also need students who have an interest in crunching numbers.”

Metz looks for students who are independently motivated and aren’t afraid of ambiguity. They have to be willing to tackle thorny problems, sometimes without direction.

“I have more experience,” Metz says, “but it doesn’t mean I know how to solve every problem. I don’t have a secret solution I’m withholding from them in the interest of stimulating learning. For advances to be made, we often need to spend time together weighing the problem.”

6. Allow your team to infuse your own experience with new appreciation and insight.

Few people get to experience working at a research station in the middle of the Amazon, collect data about a barely understood forest, or see a rural Ecuadorian countryside.

“It’s a rich, intense experience,” Metz says. “I’ve been working there for many decades, and it feels like home. Every time I return, I just get back to work.

Her students also bring a fresh perspective to Metz’s processes, solving challenges she hasn’t had time to address. In one case, Metz needed photos of the forest canopy, capturing the gaps of light that might reach the seedlings below. After a series of technological problems, Metz was ready to move on, but one of her students had time to read up on the team’s camera and keep running tests. Eventually, he figured it out, and Metz has been able to train future students on the process.

“My students have made advances that I would not be able to on my own,” Metz says. “They’ve developed research spinoffs, obtained additional data sets, and arrived at solutions to problems in the field that show real initiative and curiosity.”

7. Use your own experience to provide guidance to those who need it.

Looking back on Metz’s career trajectory, every step seems intentional. A field-based course she took as an undergraduate at Princeton led to research in Panama and Kenya. Then she worked for the Field Museum before earning her doctorate in integrative biology at the University of California at Berkeley, both of which shaped her research in the tropics. She then went on to pursue postdoctoral research at the University of California at Davis before landing her faculty position at Lewis & Clark.

In the moment, however, Metz says it never felt linear; she made the best decisions she could and followed each stepping-stone.

Metz draws on that openness when counseling students who are struggling to find their own path.

Take Pruiett, who planned to be a doctor until enrolling in Metz’s introductory ecology class. Almost immediately, she fell in love with the subject and now has a position in Metz’s lab— an opportunity she says helped her see a new way to use her scientific skills.

One former student, Mason Wordell BA ’15, traveled with Metz to Ecuador and worked in her lab after graduation. Metz helped him see that graduate school and lab research weren’t his only options. Instead, Wordell has married his field research experience with his interest in community outreach, leading to a permitting and regulatory position with Portland Parks and Recreation.

“I’ve definitely gotten away from field-based work and being a primary researcher,” he says. “Now I’m in an implementation role. In my position, I see how research about trees in urban areas helps to create codes and rules in our city. I get to help people understand why we care about these organisms. My passion all stems from studying tree seedlings with Margaret in the Amazon.”

8. Through it all, maintain a life that is more than just the work.

While Metz’s work might help researchers better understand our forests and the influences of climate change, her students and colleagues often cite another way she contributes to their success: she’s a role model for juggling high-level research, teaching, and family.

That’s because Metz doesn’t hide the many facets of her own life. Her students see her slogging through mud in the Amazon, taking calls with collaborators, working on grant proposals, preparing for lectures, and taking her kids to campus events.

Wordell says his admiration for Metz’s integration of work and life is significant. “I didn’t have an appreciation for how busy adult life was when I was in college. She has two kids and goes to the Amazon every summer. She also manages two other research projects. I just can’t fathom how she does it,” he says. “She’s a superhero.”

Kim Catley is a writer and editor in Richmond, Virginia.

-

Assistant Professor Margaret Metz, Emily Schmelling BA ’20, and Masten Summerfield BA ’20 examine forest vegetation. (Robert Reynolds)Copyright 2019

Assistant Professor Margaret Metz, Emily Schmelling BA ’20, and Masten Summerfield BA ’20 examine forest vegetation. (Robert Reynolds)Copyright 2019 -

Taken from the ground up, provide a “seedling’s-eye view” of available light in the forest canopy above.

Taken from the ground up, provide a “seedling’s-eye view” of available light in the forest canopy above. -

Taken from the ground up, provide a “seedling’s-eye view” of available light in the forest canopy above.

Taken from the ground up, provide a “seedling’s-eye view” of available light in the forest canopy above. -

Ina Waring-Enriquez BA ’17 with a tapir (a mammal closely related to horses and rhinos) at the Yasuní Scientific Station.

Ina Waring-Enriquez BA ’17 with a tapir (a mammal closely related to horses and rhinos) at the Yasuní Scientific Station. -

Robin Gropp BA ’16, Mason Wordell BA ’15, Assistant Professor Metz, and Ina Waring-Enriquez BA ’17 at the base of a giant kapok tree (Ceiba pentandra) in Ecuador.

Robin Gropp BA ’16, Mason Wordell BA ’15, Assistant Professor Metz, and Ina Waring-Enriquez BA ’17 at the base of a giant kapok tree (Ceiba pentandra) in Ecuador. -

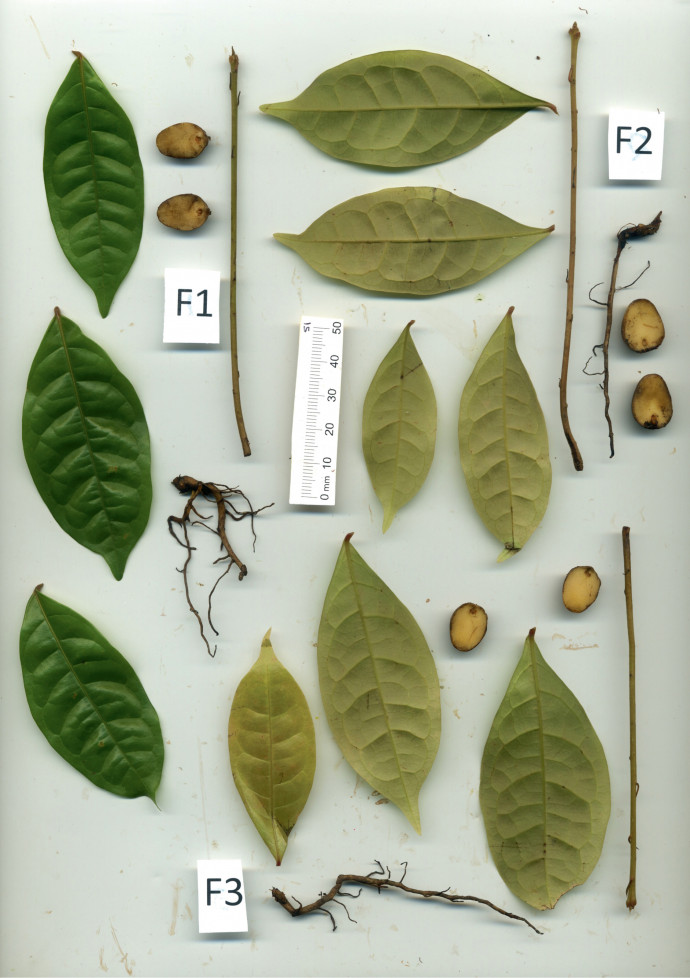

L&C researchers measure seedling parts to better understand the traits that make them successful (or not) in forest environments.

L&C researchers measure seedling parts to better understand the traits that make them successful (or not) in forest environments. -

The stilt roots of the pambil tree (Iriartea deltoidea) in Yasuní National Park, Ecuador. (Andrew Linscott / Alamy Stock Photo)Credit: Andrew Linscott / Alamy Stock Photo

The stilt roots of the pambil tree (Iriartea deltoidea) in Yasuní National Park, Ecuador. (Andrew Linscott / Alamy Stock Photo)Credit: Andrew Linscott / Alamy Stock Photo -

Emily Schmelling BA ’20, Alex Olsen BA ’20, and Assistant Professor Metz sort seed samples from their research project at the Wind River Experimental Forest in southwestern Washington. (Robert Reynolds)Robert M Reynolds

Emily Schmelling BA ’20, Alex Olsen BA ’20, and Assistant Professor Metz sort seed samples from their research project at the Wind River Experimental Forest in southwestern Washington. (Robert Reynolds)Robert M Reynolds -

Assistant Professor of Biology Margaret Metz (center), Emily Schmelling BA '20, and Masten Summerfield BA ’20 at the Hoyt Arboretum in Portland. (Robert Reynolds)Copyright 2019

Assistant Professor of Biology Margaret Metz (center), Emily Schmelling BA '20, and Masten Summerfield BA ’20 at the Hoyt Arboretum in Portland. (Robert Reynolds)Copyright 2019

More L&C Magazine Stories

Lewis & Clark Magazine is located in McAfee on the Undergraduate Campus.

MSC: 19

email magazine@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7970

fax 503-768-7969

The L&C Magazine staff welcomes letters and emails from readers about topics covered in the magazine. Correspondence must include your name and location and may be edited.

Lewis & Clark Magazine

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road MSC 19

Portland OR 97219