A Family Story: From Book to Film

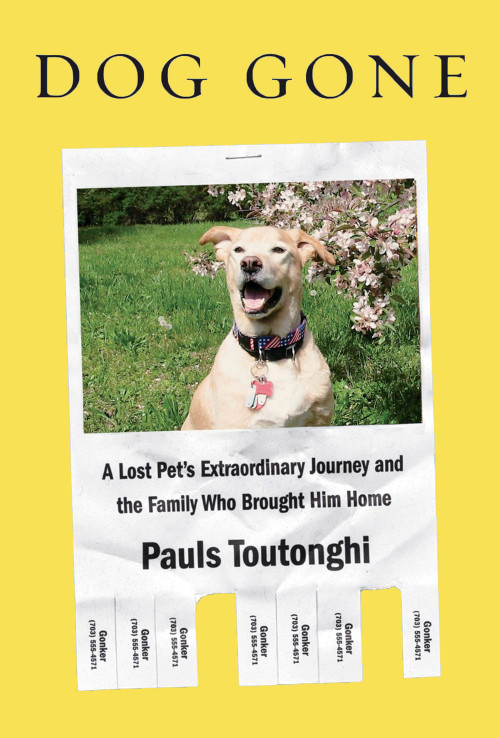

Pauls Toutonghi’s book about the emotionally charged search for a family dog is the basis for an upcoming movie on Netflix.

Open gallery

by Angie Jabine

Update: Dog Gone’s Netflix release date is January 13, 2023.

Dogs have always had star quality: Lassie, Benji, Toto, Pluto … and now, Gonker?

In 2016, Pauls Toutonghi, associate professor of English, published Dog Gone: A Lost Pet’s Extraordinary Journey and the Family Who Brought Him Home. It tells the true story of Gonker, a goofy but beloved dog with Addison’s disease who got lost on the Appalachian trail in October 1998. The heartbroken family had only 23 days to try to find him and administer a lifesaving shot. As the father and son searched for Gonker, the mother began contacting every shelter, community center, and media outlet in the region, and soon legions of dog lovers were on the lookout for Gonker as the clock ticked down.

Toutonghi’s connection to Gonker’s real-life family is personal: he married into it. Virginia and John Marshall, the parents in the saga, are his wife Peyton Marshall’s parents. Fielding Marshall, the son in the story, is his wife’s brother.

“This was the Marshalls’ famous family story,” he says. “When they told it to me, I was really captivated. Ginny is a great storyteller in person, and so is John, actually. The two of them together are just kind of a force of nature.”

Toutonghi’s original plan for the story was to write it down and present it to the family as a Christmas gift. But as he talked about it with his mother-in-law, Ginny disclosed more and more of her own painful memories—of parental abuse and a cherished dog named Oji, who was her only solace as a girl. He began to understand that the urgency of her drive to rescue Gonker had been part of a much deeper story, and what started as a Christmas gift expanded into a published book.

Dog Gone’s journey from book to film began with a writer/producer named Nick Santora, who happened to read the book, contacted Toutonghi, and asked his permission to pitch it to Netflix. Toutonghi, who already had too much work on his plate, told Santora to go ahead and pitch it, which he did, reportedly with tears in his eyes.

“I’m not sure how it came about, but Rob Lowe also really loved the material and was excited to do it. I was shocked,” Toutonghi recalls. “Lowe played Sam Seaborn on The West Wing, one of my favorite shows ever, so that was just surreal.”

Toutonghi sold the book option and film rights to Netflix, and Santora, whose writing credits include several films and episodes of The Sopranos and Law & Order, wrote the screen adaptation. Toutonghi is contractually restrained from sharing too many production details, but the story portrays both family dogs, Oji and Gonker, and emphasizes how the desperate search for Gonker became a father-son bonding experience for John and Fielding Marshall, who was concealing an illness that nearly killed him during the ordeal.

The film was shot last summer on Stone Mountain in Georgia, near the southern end of the Appalachian Trail. Pauls and Fielding spent a day on the set. They didn’t get a chance to meet Lowe that day, but both of them appear in the film as extras—which was not without its bumps.

“I ruined a shot!” says Toutonghi. “The one thing you’re not supposed to do as an extra is look in the camera. And for the shot they were doing, the camera was positioned immediately over Fielding’s shoulder and I had to sit there facing him. To complicate things, Gonker was there, and his trainer was getting him to do a trick. There was all this commotion, and somehow I glanced into the lens, and somebody yelled, ‘Background mistake!’ So they had to start the take all over”—no small matter on a 27-day shooting schedule. He takes comfort in knowing that his onscreen time will be measured in seconds.

Toutonghi acknowledges he was a bookish teenager, but he did not grow up anywhere near Milwaukee or Butte. His father was Egyptian, not Latvian, but he didn’t abandon Pauls to be raised by a single mother. When readers jump to such conclusions, the author simply takes it in stride. “It’s funny. I think in novels, there is this real desire to believe in that first-person ‘I’ as being the author,” he says. “We want to know, ‘Are stories true?’ And if stories seem true, then we want to ask, ‘Well, but if this isn’t a true story, how come it seems so true?’” He counts such reactions as a success.

The facts are, Toutonghi himself grew up in Seattle, his mother was Latvian (he speaks Latvian and is very involved in Oregon’s Latvian community), and his father was Egyptian. Toutonghi jokes that he grew up in such an ethnically divided household that he felt the need to write two coming-of-age novels, “one for each side of the family, I guess.”

Unlike his parents, Toutonghi’s life’s journey took him east at first, not west. He attended Middlebury College in Vermont, where he earned a BA in 1999. Then he entered a program at Cornell University, where he earned an MFA in poetry in 2002 and a PhD in English literature in 2006.

In 2007, he joined the faculty at Lewis & Clark, where he draws on his own experience as an author to encourage students in literature and creative writing to explore the arts and produce their own work, whether in fiction, poetry, or screenwriting.

“I think the arts at Lewis & Clark are really about trying to bridge different artistic disciplines,” he says. “We’re trying to encourage students to take advantage of the fact that we have all of these artistic resources here. So we want them to take screenwriting, to do creative writing, to take classes in the music department, to take sculpture. I think it helps the student-artist develop.”

A firm believer in supporting his students’ career aspirations, he’s currently in the midst of collaborating on several film scripts with Lars Steier BA ’10, a history major who went on to Northwestern University, where he earned an MFA in writing for the screen and stage.

Steier, who now lives in Los Angeles, took only a couple of classes from Toutonghi, but he recalls his teaching demeanor as “precise, almost mathematical.” He says what really stuck with him about Toutonghi’s creative writing class was “the idea of storytelling structure and thinking about what the conflict of each scene is.”

Steier remembers his professor occasionally taking a theatrical approach. “He actually had one class where he brought in a guest lecturer and they got into an argument because the guest lecturer was getting sidetracked,” Steier recalls. “And as it went on and they became more argumentative I realized—I think later than every one of my classmates—that it was a fake argument constructed to show the importance of conflict.”

Steier describes his collaborative process with Toutonghi as fun and casual. “Since we haven’t lived in the same city the whole time that we’ve been collaborating, we tend to send a draft back and forth,” he says. “We don’t really have a division of labor, and I think we both try to adjust our writing style so that each of us is writing in a voice that becomes both of us.” So far they’ve moved three projects into development, only to see them foiled by COVID-19 and other factors. But they persevere.

For now, Toutonghi has his hands full with his long-distance collaborations, his own writing, his Lewis & Clark course load, and the care of his young twins, Beatrix and Phineas. Oddly enough, the family doesn’t currently own a dog; Toutonghi says their two cats are far too territorial.

It’s a truly literary household. Toutonghi’s third novel, The Refugee Ocean, will be published in spring 2023 by Simon & Schuster. His wife, Peyton Marshall, author of the 2014 novel Goodhouse, recently won a 2022 National Endowment for the Arts grant to help complete her next book. It doesn’t seem like a stretch to speculate that the family’s storytelling urge will continue into the next generation.

Angie Jabine is a Portland-based freelance writer.

Setting the Stage for Film Careers

Lewis & Clark students who aspire to careers in the entertainment industry often pursue courses in the Departments of English, Theatre, and Rhetoric and Media Studies. During the 2021–22 academic year, students could also sign up for film-related courses through the Bates Center for Entrepreneurship and Leadership.

Each year, the Bates Center offers 300-level practicums in select industries. These courses have strong academic, experiential, and preprofessional components. This past fall, the Bates Center offered a Film Production Practicum; this spring, it’s offering a Screenwriting Practicum. Both courses are taught by industry professionals.

Film producer Alissa Phillips introduced the nuts and bolts of production, from treatments to coverage to call sheets. “Besides running the show behind the scenes, producers need a head for story,” says Alissa, whose multiple credits include the comedies Moneyball and I Feel Pretty. “That means reading and watching everything, ideally with a liberal arts foundation.”

Screenwriter Fernley Phillips, a UCLA film grad whose screenwriting credits include The Number 23, starring Jim Carrey, teaches students what to do—and what not to do —in a script. “Directors are incredibly talented, and actors are brilliant,” he notes. “But you need to inspire these people through the words—and that’s called the script.” Like Alissa, Fernley encourages former students to stay in touch and not to give up on getting their foot in the industry door.

The Bates Center offers coursework, programs and workshops, industry networking, and even seed funding for entrepreneurial ventures. Lewis & Clark granted its first minors in entrepreneurial leadership and innovation in May 2021.

More L&C Magazine Stories

Lewis & Clark Magazine is located in McAfee on the Undergraduate Campus.

MSC: 19

email magazine@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7970

fax 503-768-7969

The L&C Magazine staff welcomes letters and emails from readers about topics covered in the magazine. Correspondence must include your name and location and may be edited.

Lewis & Clark Magazine

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road MSC 19

Portland OR 97219